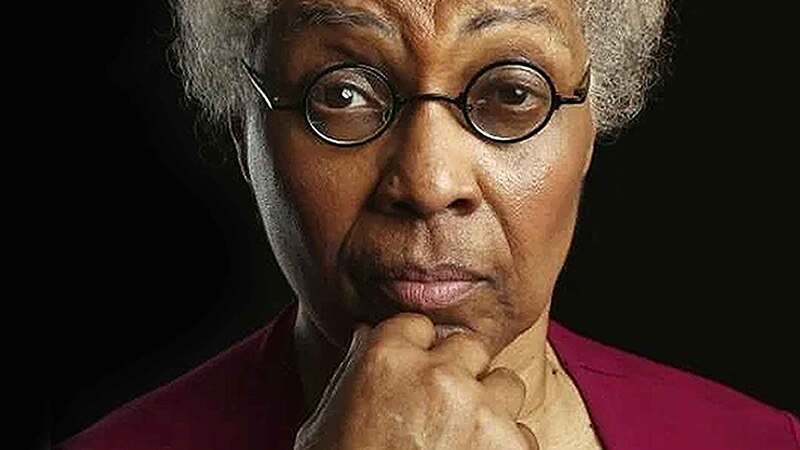

Cover art: how CEO Joanna Reynolds revitalised The Folio Society

Originally hired as a consultant in 2015 to inspect the company’s failing business model, CEO Joanna Reynolds has since transformed it into a thriving publisher.

Joanna Reynolds, CEO of The Folio Society, has shared how over the past decade she transformed the flailing reading club into a thriving company, whose vividly illustrated books are evangelised by the increasingly younger and cooler customer base.

Last year, pre-tax profit rose by 137%, reaching £1.9m, and a new edition of The Hobbit sold out in 14 minutes, with more customers now in the under-25 bracket than the over-60. This is a complete turnaround from the company Reynolds was tasked with saving back in 2015. Not long after she started, she was taken into a back room by the finance director and told they were down to the company’s last £200,000.

“It was in a mess,” Reynolds tells The Bookseller from Folio’s office in the Clove Building, a modernist warehouse near London Bridge. “Everything was in freefall – every business metric. It had been very successful, had been going since 1947. But it was still a book club. That business model was no longer working.”

Reynolds was originally asked to help in 2015 as a part-time consultant by Kate Gavron, the widow of the previous owner, Bob Gavron. Reynolds had extensive business experience across Procter & Gamble, Which?, Time Warner and Reader’s Digest and was particularly knowledgeable about direct-to-consumer businesses.

“Initially I looked at it and thought that it couldn’t be saved.” But then, while she was poring over the business metrics, one statistic caught her eye. “I found out that we’d sent out a business catalogue and got a 20% response to it. In my industry, that’s unheard of. I thought: ‘There’s something here.’”

A year on from becoming a consultant for Folio, Reynolds was made CEO. “I completely restructured,” she says. “There are some amazing people – like Dionne Crossley in the operations team, who has been here for 37 years – and Tom Walker, our publishing director, who has also been here 20-odd years. But we had far too many people, no digital team, our website was a mess, we only really used direct mail rather than any other of the direct channels.” The company went from around 60 people – “including some people who I didn’t know or never met” – to around 38.

Everything was in freefall – every business metric. It had been very successful, but it was still a book club. That business model was no longer working

“I was trying to work out what the business was about. I thought that it’s definitely not a marketing-led business – the data was much worse than when I was at Which?, for example. So I thought it must be a publishing company. It occurred to me that because the customer base was shrinking so much it was getting very introspective and very random.”

How had this happened? “No one ever left the office. And I said why don’t we go out? Why don’t we have Harry Potter? (It still annoys me that we don’t have it.) ‘Well, we’ve never asked,’ I was told. Well, then, we’ll never get.”

“We go out – try and meet publishers and lots of people outside – but also scurry away in museums... like with The Little Prince: find the original art and do something unusual, which creates a book that is unexpected but has a phenomenal story behind it.”

The reading club model meant that each customer bought four books a year – and people could only become members in the month of September. “I don’t know any other business that does this,” Reynolds says. “The whole thing was insane. I got rid of the membership and the reading club model and the customer-service team said at the end of August: ‘No one can do anything with customer services because so many people will be calling us.’ I don’t think the phone rang once.

“People want to buy our books but they don’t want to commit to buying four a year and I think that also made our publishing quite lazy. Now Tom has completely revolutionised the whole publishing programme.”

Reynolds encouraged more clarity and focus. “We had 12 different systems – fulfilment house, finance, marketing, and so on – which didn’t speak to each other. No one knew what the numbers were, it was complete chaos.” Reynolds built a digital team, revamped the website and encouraged joint working across teams as much as possible.

Continues...

Another “huge, huge change” has been the books themselves, with a more modern take. “When I started, 95% of the books were out of copyright, now 95% are in copyright. It’s not that we’ve left all the past behind. In September, we have a Jane Austen book to mark the big 250-year anniversary. But we also do SFF and are publishing Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow – so we’re still doing the old classics we’ve always done, but also the more modern stuff. And the non-fiction is a lot more exciting, a lot of it is winning prizes; the growth in that drove a lot of change.”

The company pulled out of retail because Reynolds felt the books did not fit a bookshop setting, partly because of the price point. The reaction? “I’m not sure retailers even realised we stopped being stocked there.”

The company also moved premises from a grand building in Holborn (“it was much too big and there were rooms I don’t think anyone had been in for many years”) to the smaller – though iconic – Clove House building.

The results have been dramatic. “We came into profit about four years ago and have been in profit ever since.”

There have been other major changes that have impacted the staff. In 2021, when Kate Gavron suggested the family might want to sell the business, the employee-owned trust (EOT) model was mooted; Reynolds was told by a lawyer it would take a few years to come through – she made sure it was done in three months. “On signing, we paid 40% of the evaluation out of cash in the business, and now we’ve paid off 80% and we’re hoping to sign off fully next spring. Unusually, we own the business equally and share the profits equally. I was invited to LSE recently to talk about the business because they were interested in how it works.”

Folio is a lot more international these days, with a bigger customer base in the US as well as surprisingly big readership in places such as Germany. Reynolds visits America twice a year, as well as Australia and Europe, to run focus groups to see how people read the books.

“We have ambitions to grow the company; there may be a few people coming in. But one of the things I started asking myself six months ago, when I thought Trump would get in, was: ‘Do we get a separate US entity over there?’ We’re having discussions about that now... the global situation for all businesses is quite terrifying.”

Other complications include the thorny post-Brexit supply chain, the tussle for rights (“we’ve waited 10 years for some books”), perfectionist artists who take longer than was hoped. But Reynolds is focused on keeping the business profitable and leaning into the high-end nature but steering clear of exclusivity.

“We were a business that wanted to put books on bookshelves and it was distant and not emotional and I thought, I don’t want people to put away our books,” she says. “I want people to read the books and enjoy them.”