You are viewing your 1 free article this month.

Sign in to make the most of your access to expert book trade coverage.

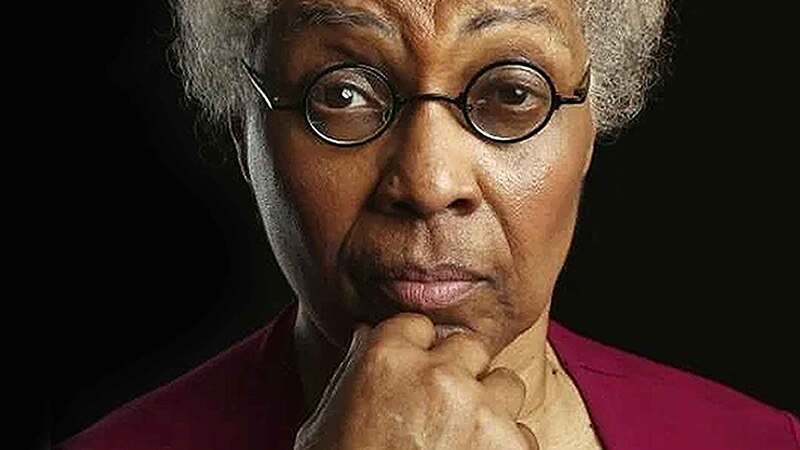

Sophie Goldsworthy: ‘We’re a counterweight to propaganda, conspiracy and the erosion of truth’

Oxford University Press’ new academic boss on its mission to elevate public discourse in the fake-news age of Trump

When I meet Sophie Goldsworthy, one of the first questions I pose is whether this is the most challenging time in the history of university presses (UPs).

It is a slightly outlandish question for the new Oxford University Press (OUP) global academic publisher. UPs play a long game, as they have been around for a long time: OUP since 1598, and one imagines the sieges of Oxford by Parliamentary forces during the English Civil War might have put a dampener on the University Press Weeks of the mid-1640s.

But current times are difficult. The strained budgets of universities and governments have a two-pronged bite: most UPs exist as departments within universities and their content is dependent upon well-funded research; and UPs’ core customers tend to be academic institutions and libraries whose spending power in many territories is now heavily constrained. Plus, artificial intelligence (AI) has upped the digital ante where questions of copyright protection and AI’s impact on research are just the tip of the complex issues around its use.

‘Our publishing reasserts the value of expertise by foregrounding authors at the top of their games globally, helping them develop their research’

A rummage through the most recent full-year financials via Companies House, universities’ annual reports and the Charity Commission shows that British UPs are feeling the pinch. In the mid-level, players like Yale UP had an income slip of 1.4% to £8.73m, while Edinburgh UP’s contracted 6% to £4.8m. The Oxbridge behemoths have not been immune. OUP’s headline turnover declined by 4.5% and its profit was down 38%. (This is relative; OUP’s decreased turnover was £795m and the profit £61.4m.) Cambridge University Press & Assessment (CUPA) had a slight jump of 1.2% to £1.04bn, but its profit dropped 13%, to a “mere” £205m. But a commonality in all these UPs’ annual reports, no matter the size, was the noting that tough trading conditions had impacted their businesses.

Profit-and-loss reports and market forces are only part of the story. Yes, UPs want to make a tidy return for parent institutions. But the core is the dissemination of high- quality research to the widest possible audience to promote learning and culture. But disseminating that knowledge is now deeply under threat from geopolitics and culture wars. Particularly by the fake-tanned vulgarian in the White House and his MAGA cronies’ so-called “war on universities” in America. The US has an outsized role in world research, so the Trump administration’s bullying and threats of defunding institutions that do not fall in step with its hard-right views will hit UPs’ content across the globe.

This comes amid the general climate of our post-truth, fake-news world in which the public might trust a TikTok huckster more than an academic with a wall full of degrees. Can UPs get the world to listen to experts again? Can the sector ever recover from the age of misinformation?

Goldsworthy does not disagree that the climate has made UP publishing more difficult – but argues this just makes the mission more vital. She says: “It’s a fraught time and we are obviously facing political volatility and cultural fragmentation, left, right and centre. I think there are a number of ways in which the publication of serious non-fiction can help counter the polarisation where expertise is often dismissed or politicised. Serious non-fiction offers a platform for rigorous and evidence-based thinking. Our publishing is reasserting the value of expertise by foregrounding some of those authors with deep knowledge who are at the top of their games globally, to helping them shape and develop their original research.

“We aren’t ever trying to dumb things down. We’re inviting our readers to wrestle with complexity, not necessarily offering easy answers or AI-style summaries. Although on our platforms we are trying to use some of those tools to make content land more effectively for different types of reader. But serious non-fiction is a powerful challenge to binary thinking and helps foster a more nuanced understanding of the world [and] an effective counterweight to propaganda, conspiracy and the whole erosion of truth in public discourse.”

Continues...

Goldsworthy points out that a lot of books on OUP’s Academic list at the moment are on hot-button topics, tackling urgent issues such as AI ethics, the legacies of colonialism and democratic fragility. Indeed, its top-selling 2025-published title through NielsenIQ BookScan is the technology legal scholar Richard Susskind’s How to Think About AI: A Guide for the Perplexed. Others in the “urgent issues” space include Tim Lenton’s Positive Tipping Points: How to Fix the Climate Crisis, former Australian PM Kevin Rudd’s look at the state of Chinese politics in On Xi Jinping: How Xi’s Marxist Nationalism is Shaping China and the World, and The Colonialist, William Kelleher Storey’s reassessment of Cecil Rhodes’ ongoing, difficult legacy in southern Africa.

Let us not over-egg this. The academic division’s bread and butter remains its reading-list staples, textbook ranges such as the Oxford Medical Handbooks or Blackstone’s Statutes, and student-adjacent series such as the Very Short Introductions books. Often, the content is delivered digitally. Goldsworthy cannot reveal Academic’s turnover, since OUP does not strip out divisional financial performance. But its annual report says 76% of Academic sales came from digital, the Oxford Academic platform logged a record 187 million visits last year, while digital books content hosted on the platform increased in usage by 6%.

But OUP has made a concerted effort in the past few years to lean into its trade side – to, in CEO Nigel Portwood’s phrase, “publish with purpose”. That means, Goldsworthy says: “Curation and intention. It’s about being selective and strategic in commissioning work that will make a meaningful contribution to the cultural conversation by reaching outside the purely academic audience. Non-fiction in general is having a tough time. Inevitably, with everything that’s going on, people are looking for escapism – we don’t publish romantasy and I don’t think we ever will. But we can build bridges across audiences. Publishing with purpose means connecting with general readers, students, librarians, policymakers and coming up with inclusive messaging that will work for all of them.”

Goldsworthy was an Oxford student, reading English literature at Mansfield College, and after graduation in 1992 wanted to go into journalism but could not find a job. So she set up a freelance copy-editing business and ended up working on distance-learning manuals for the brewing industry, prayer books for small religious publishers and “a load of medical journals; I know a lot more about urology than I ought to”. One of her customers was OUP, which morphed into a full-time gig in 1995, where she has been ever since. In her three decades with the press she has worked a variety of editorial and project leader roles across the academic and trade lists, and was OUP’s director of content strategy and acquisitions for four years before stepping into her current role in April.

Goldsworthy says: “It’s never a plan to stay anywhere for 30 years, is it? But OUP is one of those places people stay a long time and, though it sounds saccharine to say, I’ve always enjoyed it. I’ve learned, been challenged and stretched every day. Plus, it feels like a privilege to be here when it is important for serious non-fiction to be something that doesn’t just inform but can also transform as a deliberate act of cultural intervention. I’d say that’s a sentiment shared across OUP.”

Sophie Goldsworthy on authors working with AI

“We talk a lot with our authors about AI, the implications in the creation of the work, and what that means for the author’s IP. What we’re trying to do is also feed into that wider conversation about where the line is: if you want to use AI, we wouldn’t necessarily not publish your work, but we would ask where it had been used, why it had been used and what steps were taken to verify the outputs.

“There are all sorts of plagiarism tools, but because the large language models contain in effect everything, it’s very difficult to ensure that [a manuscript] hasn’t been generated through AI. Springer Nature recently published a book about AI that turned out to have been written with AI and was full of inaccurate references [the now retracted Mastering Machine Learning]. I thought then: ‘There by the grace of God go any of us.’

“We also educate authors about AI because I think most authors don’t know that if, for example, they input their manuscript into ChatGPT to generate captions for their illustrations, they’ve jeopardised their own IP, as it’s being ingested for subsequent training.

“There are few easy answers. This University Press Week is my 30th anniversary at OUP and I’ve never known the ground beneath us to change as fast as it is shifting at the moment.”