You are viewing your 1 free article this month.

Sign in to make the most of your access to expert book trade coverage.

Library bodies wrangle censorship question but warn of deeper issues

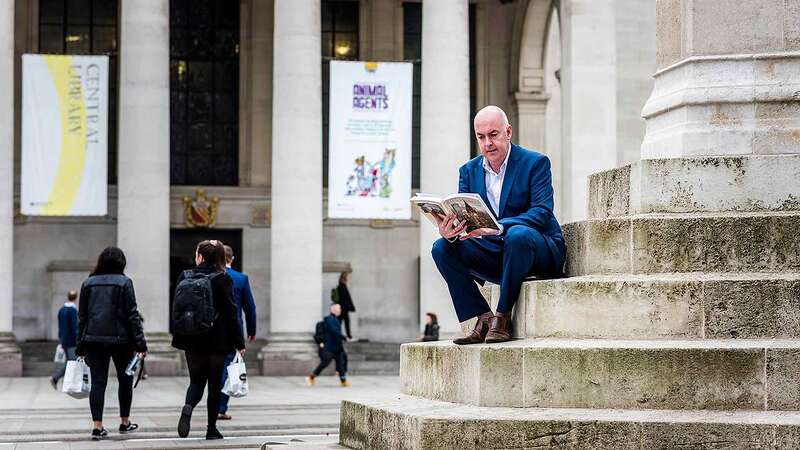

In August, the Chartered Institute of Library and Information Professionals (CILIP) launched the Intellectual Freedom Committee to help library professionals “counter the disturbing effects of censorship”. The group is headed up by Dr David McMenemy, reader in the School of Humanities in Information Studies at the University of Glasgow and the current CILIP Scotland president.

“I firmly believe that this new committee needs to see and understand the challenges to intellectual freedom in their full complexity,” McMenemy says. “It can then reinforce our profession’s commitment to intellectual freedom as being at the heart of our contribution to society, before we then advocate to others about this fundamental right.”

The committee launches against a fraught – predominantly US – backdrop, where legal challenges have been brought against, for example, a Florida law that came into effect in 2023 and banned books that “describe sexual content” in school libraries. Books that were removed under the law reportedly included Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, Toni Morrison’s The Bluest Eye and titles by Julia Alvarez, John Green, Jodi Picoult and others. A federal judge recently ruled that the part of this law used to remove books was “overbroad and unconstitutional” in what was heralded as a “sweeping victory for the right to read”, but “worry” still remains, says CILIP chief executive officer Louis Coiffait-Gunn.

“There’s a lot of worry, partly because of the rhetoric in the States, partly because of the anecdotal stuff,” he says. UK Reform-led Kent Libraries made headlines in July after claiming that transgender-related books had been removed from children’s sections of its libraries. (It turned out, Coiffait-Gunn says, “that was a pack of cards. The book wasn’t in the children’s section, it was in an adult section”.)

Elsewhere, the National Library of Scotland recently came under fire after it excluded a “gender-critical” book from an exhibition about books that have “helped to shape our country”. CILIP Scotland released a statement that, in part, said: “We understand that the book in question has not been banned and is permanently available to read for free within the library, as well as being included within the exhibition space in a catalogue of all Scotland’s Books That Shaped Me. We welcome this as library professionals are committed to ethical principles that support access to knowledge and intellectual freedom, and we would be firmly against the censorship of any book lawfully published.” After conducting an internal enquiry, on 5th September the BBC reported that the book had been readmitted to the exhibition.

Coiffait-Gunn adds that “[removing books is] a lot more acute in schools because there’s a lot less scrutiny”. Victoria Dilly, CEO of the School Library Association, says: “For many children and young people, the school library is the only place they can access books that will help them to develop empathy, a sense of identity and belonging. Removing access to books damages every child’s ability to understand the world they’re growing up in.

We’re having ongoing conversations across the school library community and with educators to seek ways to address the issue of censorship, which has been an ongoing concern of the profession.”

For Coiffait-Gunn, the debate – across the spectrum of libraries, from school to public – coalesces primarily around trans rights. “When people talk about censorship, they’re talking about trans rights,” he says. “That’s about 80% of the issue, from what we see. We’re not in this place in America where parents or public-library users are complaining about books about race or something like that. We’re not in that position, thank God. And I don’t think there’s that much explicit homophobia, for example, or anti-LGBT+ generally. But often a lot of the trans debate has a kind of implicit anti-LGBT+ rhetoric around it, I think. But yeah, that is the number one issue. That’s what everyone talks about.”

Continues...

However, Coiffait-Gunn says “there is no strong evidence” of outright censorship in UK libraries. Isobel Hunter, CEO of charity Libraries Connected, agrees. “In the UK, public libraries’ attempts to have books banned or removed are still fairly rare, and they tend to be requests by individuals rather than the organised campaigns that we’ve seen in the US that have been sweeping through whole sets of books. “In Britain, the intellectual freedom of libraries is well established. There’s some defence in the Libraries Act around being comprehensive and efficient and the wide range of book stocks.”

This year marks the 175th anniversary of the original Public Libraries Act 1850, which was followed by the Public Libraries and Museums Act 1964. The latter stipulates that “it shall be the duty of every library authority to provide a comprehensive and efficient library service for all persons” and that libraries will keep “adequate stocks” that are “sufficient in number, range and quality to meet the general requirements and any special requirements both of adults and children”.

Libraries Connected has also “just drawn together some guidance for public libraries about the legal and ethical professional basis to things like book stock selection”. On the dearth of evidence beyond the anecdotal, CILIP is currently “in conversations with funders and publishers about doing some proper research” as “every trade publisher should be talking to us, because they should care about this issue”. Coiffait-Gunn continues: “There is a lot of anecdotal evidence and some very small qualitative, non-representative surveys, some of which CILIP has been involved with. [And] obviously any one example is one too many [but], in many ways, the censorship issue is a very minor distraction.”

It is also nothing new, as McMenemy writes in CILIP’s membership magazine Information Professional: “When it comes to censorship challenges in libraries, there is rarely anything we have not seen before as a profession.”

He cites numerous examples, such as the 1910 withdrawal from circulation by the Beverley Public Library of the novel Ann Veronica by HG Wells – “a story about an emancipated young woman during the time of the suffragettes”. In 1913, he goes on, Henry Fielding’s Tom Jones was banned in Doncaster after “extracts were presented [to the library committee], some indecent, impure and objectionable”. McMenemy quotes US librarian Jo Godwin: “A really good library has something in it to offend everyone,” and ultimately concludes that “as a profession, we should never seek to be on the side of repression or even the wrong side of history, but equally, if material is legal and a patron wishes to access it, we must consider that request in good faith”.

Coiffait-Gunn echoes the sentiment that “none of this is new”, and argues that “the much bigger story is the [library funding] cuts, because that is basically just closing libraries, removing professional staff, reducing budgets, reducing book stock, reducing hours”. He adds: “Censorship is then a debate about one or two titles within what’s left. So, in terms of priorities, the number one issue is funding and shrinking access for citizens, despite the Library Act [which is] supposed to guarantee access.”

Laura Swaffield, chair of The Library Campaign, agrees: “I’m rather more worried that cuts to book stocks. That is another way of banning books and that’s much more widespread.” She adds: “I don’t think there’s anything sinister behind it, but the results are equally sinister. If you’re looking to cut your book stock you probably will cut the more fringe, the more unusual, the more challenging stuff, and you’ll obviously stick to providing the stuff that everybody wants, the bestsellers and the crime and the romance and all of that. Nothing wrong with them, of course, but I think a lot of the interesting stuff is probably going to suffer.” “They’re hollowing out the library service.” Coiffait-Gunn adds: “Having that breadth of collection and allowing people to follow a wider range of interests, a lot of public libraries are getting squeezed, and that includes their stock.”

What it boils down to for him is government failure to properly provision the library service. “No ministers since 2010 can say that they’ve left the service improved, which is one of their statutory duties,” he explains, adding that CILIP was disappointed by Labour’s Chris Bryant – whose vast ministerial sciences and creative industries portfolio included libraries – who “came in [under Keir Starmer], and although he wore lots of hats... [was] supposed to champion the sector”.

However, “he didn’t visit a single library between July and, I think, April, when he was in post”. There is hope for his successor Baroness Twycross, who “has been much more engaged, has more time, has visited lots of libraries” though Coiffait-Gunn says CILIP sent her an updated version of the plan for libraries Bryant asked for, “but that was in May, so the clock is slightly ticking”.

He continues: “There was a libraries debate in the House of Lords last October [and in the] House of Commons in May 2025. We helped drive both of those debates. You’ve got loads of support from across both houses for public libraries, and there was a real demand for an ambitious strategy from the government. But where is it? It’s still not here.”