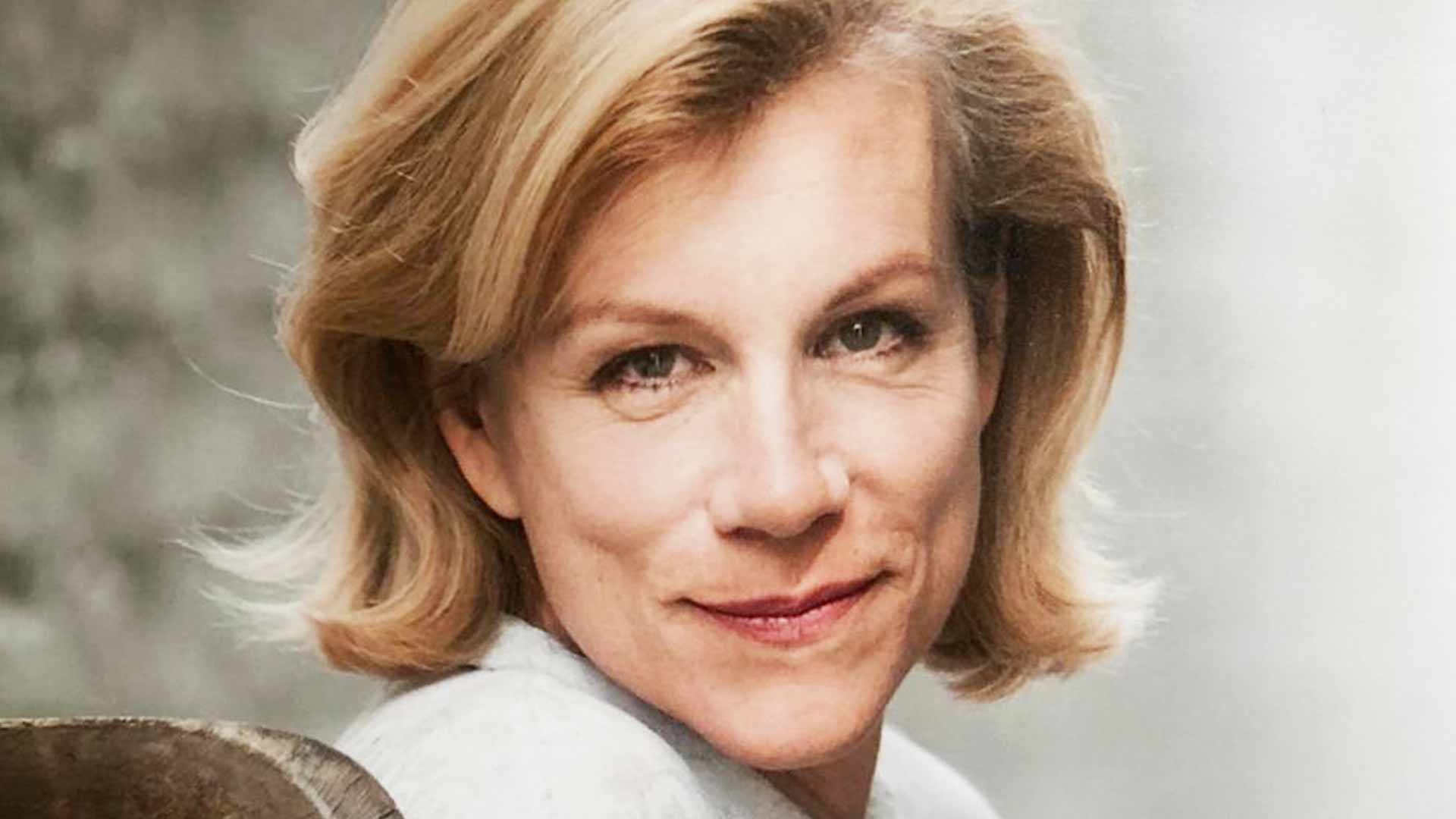

Speakies shortlistee: Juliet Stevenson (Persian Pictures)

Juliet Stevenson

Register to read for FREE.

Serious about the book trade?

Join thousands of book industry professionals who never miss a story.

Create a free account to unlock 3 articles a month and receive tailored newsletters with the latest from the book trade.

Want full access? Subscribe from just £3.65 a week and unlock full access to exclusive interviews, rights deals, industry data and more:

🗞Weekly print copies of The Bookseller magazine

📱Unlimited access to thebookseller.com (single user)

👨💻The Bookseller digital edition for desktop, tablet and mobile

💌Subscriber-only newsletters

📚Twice-yearly Buyer’s Guides worth £30

💡Discounts on events and conferences