Far from basic

Ireland’s basic income for the arts could be a game-changer for creatives.

Like the country’s geography, Ireland’s cluster of creative industries forms a small island bordered by the overbearing masses of two much larger, English-speaking neighbours. It does mean that we get to enjoy the products of their creative industries without translation and can more easily sell ours to them, but it also means we are competing with them in our own market, one so small that it is next to impossible for artists to make any kind of living in it. As an author, for instance, I could make the bestseller lists every year and never make minimum wage for my work.

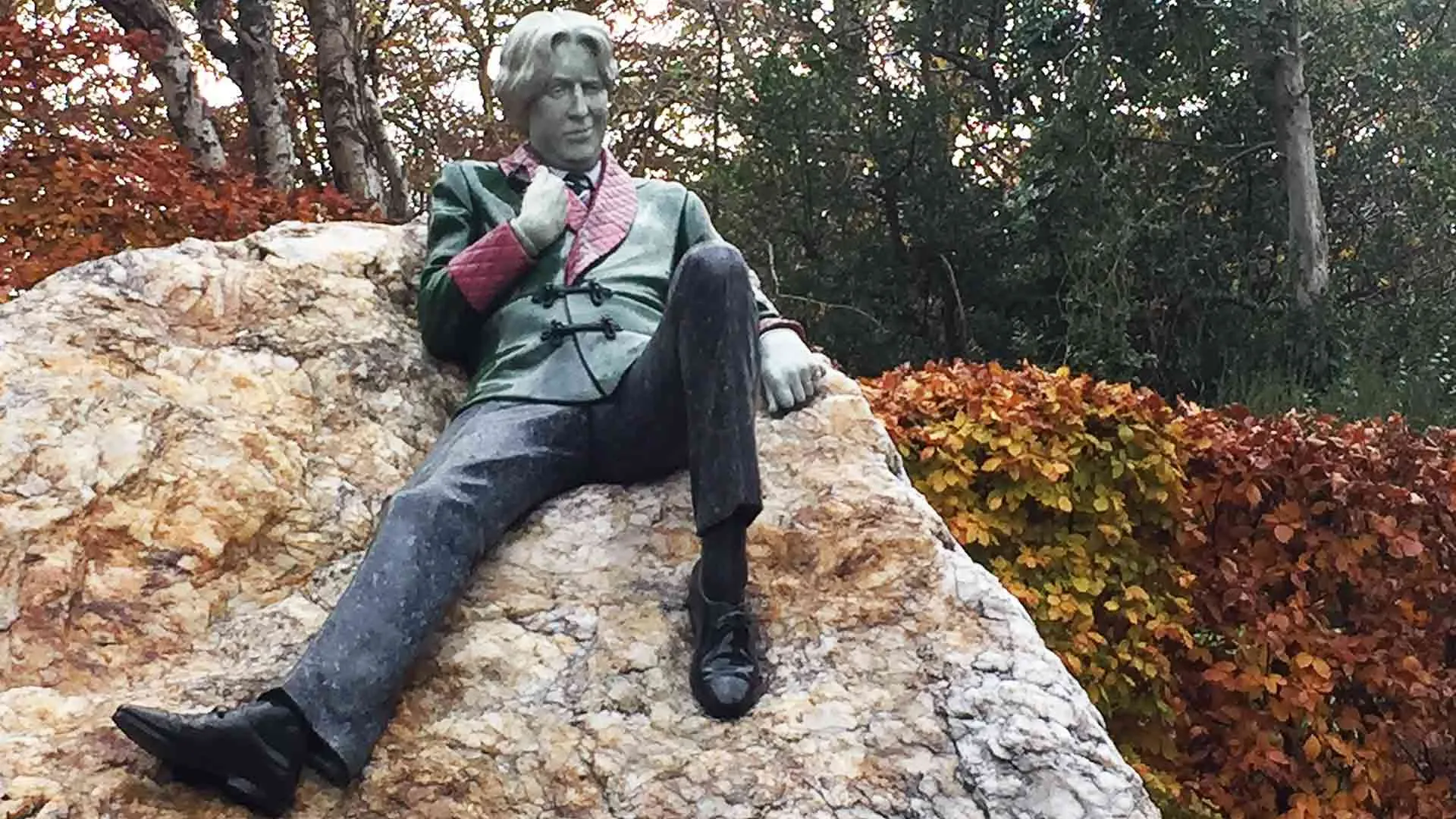

At the same time, Ireland does have a cultural reach that belies its size – the oft-repeated phrase is "we punch above our weight". Some of this is down to the fact that we’re an English-speaking nation, some is because of support from organisations such as the Arts Council and local authority arts offices. Another major factor is Ireland’s tax exemption for artists, introduced in 1969 to counter the mass exodus of artists from the country, who were forced to seek opportunities elsewhere. Ireland was being drained of its creativity.

The tax exemption for qualifying creative work, now capped at €50,000, seems like an extraordinary boon until you look at the arts as a whole. Whenever governments have considered getting rid of it, the numbers have spoken for themselves; the value of the arts to our economy hugely outweighs what could be gained by taxing artists’ creative income. Let’s take publishing as an example: while publishers here are often supported by Arts Council funding, by far the greatest subsidy comes from writers, and to a lesser extent illustrators, through the vast amount of work they provide for free, and from which publishers can pick and choose what they like, without ever having to pay a living wage for it. Those artists, who often have to make their money in other jobs in order to provide this free labour to publishing, are the only workers who cannot realistically expect to make a living in an industry whose existence is based on their work. This means that, instead of being treated as workers with rights, they are more like a resource that can be mined, and you do not pay the ground for its gold. A tax exemption is only valuable if you are earning money.

This situation is common across the creative industries, where businesses ride along a road paved with the careers of discarded artists. Unable to change this capricious system of work, Ireland has struggled to maintain a professional class of artists. Sooner or later, most people either leave the country or just give up.

Ireland has struggled to maintain a professional class of artists. Sooner or later, most people either leave the country or just give up

In April 2022, the Department of Culture, Communications and Sport invited applications for its Basic Income for the Arts Pilot Scheme. Participants would receive a payment of €325 per week, the number would be limited to 2,000, and while you had to meet set criteria to qualify, the payments would not be conditional on any kind of work. A number of unsuccessful but eligible applicants were asked to participate in a control group to help with the evaluation of the pilot. Control group participants were asked to respond to the same survey and data requests as those in receipt of the payment, and were paid two weeks basic income for each of the three years of the pilot scheme to compensate them for the time and effort.

According to the surveys and follow-up interviews with 50 of the recipients, the effects for many were life-changing. In May of this year, Minister Patrick O’Donovan said: "This research shows that the impact of the basic income is far-ranging and affects all aspects of recipients’ lives… Artists are investing more time and more money into their practice, completing more new artistic output, experiencing reduced anxiety and are protected from the precariousness of incomes in the sector to a greater degree than those who are not receiving the support."

The committee of the National Campaign for the Arts, who have done extraordinary work in pushing for this, said: "This qualitative report clearly demonstrates that the BIA has helped to sustain individual creative practice, boost ambition and creative outputs, as well as strengthen artists’ connections to their local communities. In addition, the pilot scheme has supported artists to secure more sustainable housing, address health issues, start families and even establish pension schemes. The findings affirm what the arts sector has long known: the deep precarity of the arts requires sustained, courageous support – support that not only transforms the lives of artists, but also strengthens the society they help to shape."

The pilot scheme was due to end in August this year, but in June, Minister O’Donovan announced a six-month extension for the current recipients as the government looks into taking it further. Beyond what that would mean for the arts in Ireland, there is something more to consider: this is a test run for Universal Basic Income. Providing this scheme for artists is a slightly more palatable version of the concept for those who would oppose UBI. Artists are by definition, identified by their work. And it is the fear of people not working that opponents play on when they argue against UBI, so providing it to artists is at least something they can get their heads around.

And in the meantime, the Basic Income for the Arts would create opportunities for those who might otherwise never break through at all, to have a chance to find their audience. It could also provide much-needed support for all the artists who enrich the lives of people in Ireland, and who are so often left behind after their careers have been mined by others for everything of worth.