You are viewing your 1 free article this month.

Sign in to make the most of your access to expert book trade coverage.

Natalie Haynes on challenging patriarchal historical narratives and championing female voices

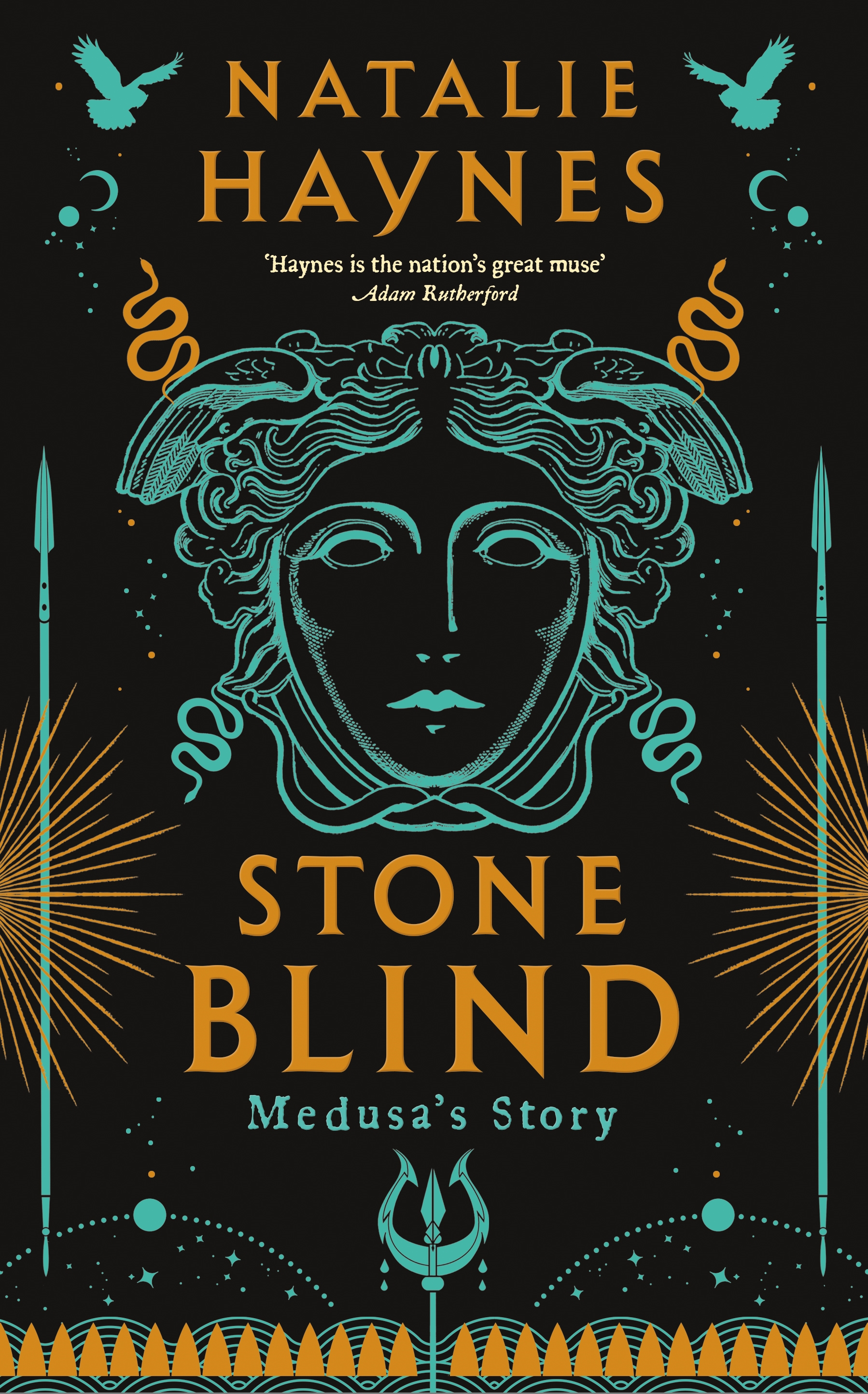

Natalie Haynes’ previous novel was shortlisted for the Women’s Prize in 2020. Her latest book tackles the Medusa story through a feminist lens.

"I do love to take a story that you sort of know and tell you that it hasn’t always been the way you know it to be,” says Natalie Haynes, a self-declared “classics nerd” who has made her career reinventing Greek myths for a modern readership. As befits a former stand-up comic, she is sharp as a tack and very funny when we meet at a hotel bar in central London on a sunny afternoon.

Her previous novel, A Thousand Ships, a retelling of the Trojan War from the point of view of the women involved, was shortlisted for Women’s Prize for Fiction in 2020. Her latest tackles the Medusa story through a feminist lens and is, she says, “an attempt to retell the story of a woman who was viciously abused and assaulted and to see her neither as a monster, nor as a victim but as a person.”

Medusa had her own chapter in Haynes’ non-fiction title Pandora’s Jar: Women in the Greek Myths but the author knew there was more to say: “I was still so angry for her at the end of it. Generally the act of writing what is effectively a 10,000-word essay would get it out of my system, but I was just really cross.” So Haynes decided Medusa deserved her own novel: “If I feel this strongly about you, having given you your story back, I probably have unfinished business with you!”

You can’t move for an account of the Trojan War in Latin or in Greek but with the story of Medusa there was a lot more space for me to fill in the gaps

The result is her compelling fourth novel, Stone Blind, which takes the story we think we all know—of the fearsome snake-haired Gorgon beheaded by the hero Perseus—and rips it to shreds. We meet Medusa as a baby, left on the Libyan shore outside the cave where her sisters dwell, by her father Phorcys, an old god who lives in the depths of the ocean. Her Gorgon sisters Sthenno and Euryale are immortal, but Medusa is not, so she is the only mortal growing up in a family of gods.

As a young woman Medusa is followed into the sacred temple of Athene by Poseidon, god of the sea, who commits a terrible act. Athene, furious at the sacrilege, takes revenge not on her uncle Poseidon but on the innocent Medusa, by turning her human hair into snakes and cursing her with a terrible power; a gaze that will turn any living creature to stone. Appalled, Medusa retreats to her cave, unable to look at the sisters she loves and who love her. Meanwhile, far away, Polydectes, King of Seriphos, sends Perseus on a quest to bring back the head of a Gorgon…

Cracking pace

Stone Blind unfolds at a cracking pace with short chapters from the perspective of multiple characters breathing new life into this nearly 3,000-year-old tale. I wonder if the energy of her storytelling is a benefit of having done stand-up comedy for over a decade; she knows how to hold the reader’s attention. “I think it’s an unusual combination of knowing Aristotle’s Poetics which tells me how to structure drama in order to keep tension building, and also knowing exactly how patient the late-night audience is at the Comedy Store. Which is not very patient.”

Haynes’ characters, both mortals and gods, are wholly rounded. These gods are capricious, vexatious, spoilt and demanding and, in the case of Athene, bitingly funny. The scenes where Athene and Hermes attempt to help Perseus—who is not so much a brave hero but a hapless incompetent, wildly unsuited to the task—are terrific. The other characters are wonderful too, the bad-tempered Graiai, three sisters who share a single eye and one tooth between them; vain Cassiope, queen of Ethiopia whose daughter Andromeda will pay the price for her mother’s belief that she (Cassiope) is a beautiful as a goddess; and the Nereids, 50 sea nymphs “of changeable temper”.

With female characters… you’ll just get this very brief account of what we would consider to be an earth-shattering event

There are surprisingly few written sources about Medusa, Haynes tells me. She began learning Latin aged 11 at school in Birmingham, and Ancient Greek at 14 before reading Classics at Cambridge and so always returns to the original texts. “You can’t move for an account of the Trojan War in Latin or in Greek but with the story of Medusa there was a lot more space for me to fill in the gaps.” Medusa gets a brief mention in Hesiod’s “Theogony”, the epic poem describing the origins of the Greek gods, composed circa 700–730 BC. Ovid’s Metamorphosis, written in 8AD, has more detail, although the whole story is from Perseus’ point of view. “Especially with female characters… you’ll just get this very brief account of what we would consider to be an earth-shattering event,” observes Haynes. “So, in a way, it’s joyous, because what you have is this skeletal framework and all these people in the shadows that you get to fill in and bring forwards.”

Stone Blind is her first novel since A Thousand Ships, which was nominated for the Women’s Prize. “My mum said, when it took me so long to get started on this one, ‘I worry there’s more pressure on you because of the Women’s Prize shortlisting’ but in the old days the pressure was ‘will anyone publish my book?’ That’s so much worse than ‘will people expect my book to be good?’ I come from stand-up; if people expect you to be funny, they find you funny. If people are expecting your book to be good, they’ll probably like it better than one they might not even pick up. I’ll cope with this pressure—it’s fine, thanks!”

A Thousand Ships had done well in the UK but not sold anywhere else, most painfully in America. “Everyone in New York had turned down Ships” remembers Haynes. “For a while my agent and I had a joke that if you wanted a job in publishing [in the US], you would be asked if you would publish Ships and you would have to say no and then they’d give you the job.” The shortlisting changed all that, and Pandora’s Jar, which had previously been rejected US publishers, was snapped up too and ended up on the New York Times bestseller lists.

Feminist viewpoint

“I was asked when Ships came out, in a radio interview, if it was a bit anachronistic to centre the story around the women. I said, I hear what you’re saying but of the eight tragedies Euripides wrote about the Trojan War that survive to us today, seven of them have female title characters. So if it is anachronistic, he didn’t get the memo.” Indeed, a feminist viewpoint is long overdue in Haynes’ opinion: “They had a couple of centuries of untrammelled patriarchal interpretation, it’s about time they made a bit of room.”

And room is being made on the bookshelves. Feminist retellings of Greek myths are now a distinct sub-genre of historical fiction with novels set in the ancient world from Madeleine Miller, Pat Barker and Jennifer Saint all hitting the bestseller lists, and many more contemporary novels based on Greek plots, such as Kamila Shamsie’s Home Fires. “The great delight of Greek myth is that there’s so much of it, and it’s so detailed and so human-centric but the women’s stories have not really been told. So they are right there! And if, like me, you spend your entire life basically swimming around in Greek myth, there’s just not a shortage of these stories, I could do them forever. That sounds like a threat, I realise…”