You are viewing your 1 free article this month.

Sign in to make the most of your access to expert book trade coverage.

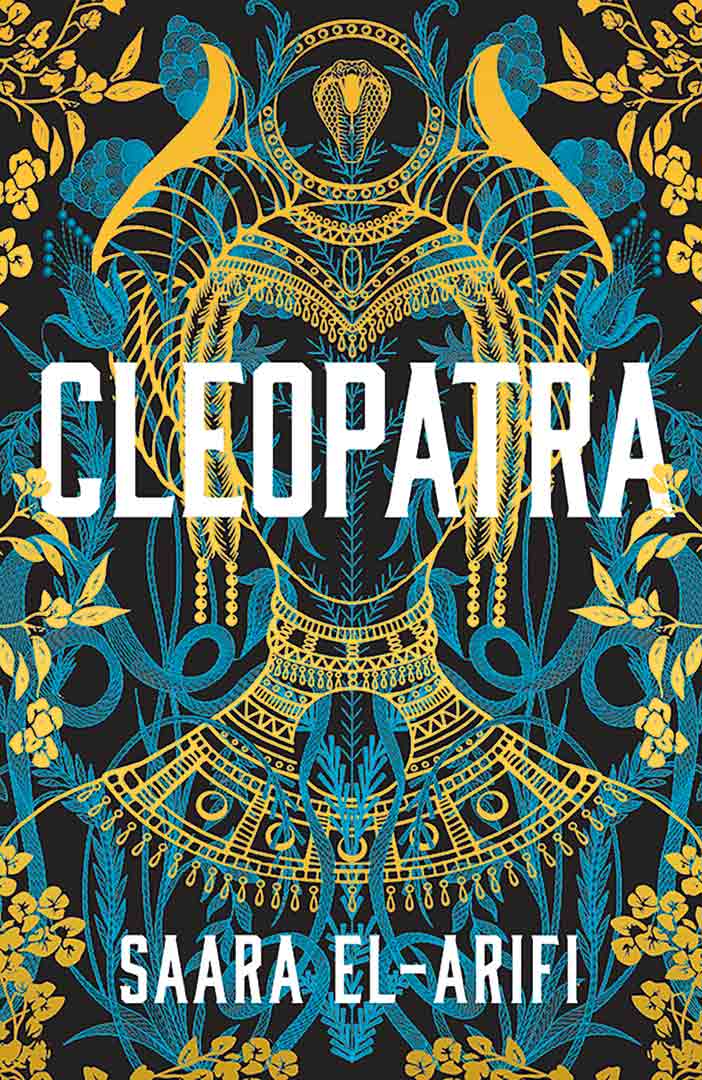

Nibbies Pageturner winner Saara El-Arifi sets out to connect Cleopatra to modern womanhood

Katie Fraser is The Bookseller's staff writer and chair of the New Adult Book Prize. She has chaired events at the Edinburgh International

...moreIn Saara El-Arifi’s first historical fiction novel, she seeks to connect the voice of Egypt’s last pharaoh with contemporary experiences of womanhood.

Katie Fraser is The Bookseller's staff writer and chair of the New Adult Book Prize. She has chaired events at the Edinburgh International

...more“You know my name, but you do not know me. Your poets have sung about my tainted crown, your bards have spoken on my infinite variety.” These are the opening lines to Saara El-Arifi’s latest novel, Cleopatra, her first foray into historical fiction.

Since the publication of her epic fantasy debut The Final Strife in 2022, El-Arifi has gone from strength to strength. Earlier this year, she took home the Pageturner Book of the Year Award at The British Book Awards for Faebound, the first in a romantasy series that will conclude next year with Earthbound. In her acceptance speech, she said: “I didn’t prepare anything because I thought ‘listen, this is not going to happen’ because there are a lot of barriers for people like me: I’m Black, I’m queer, I’m a woman… You guys in the room can bring those [barriers] down.”

Cleopatra is El-Arifi’s best yet. Pairing exquisite prose with a propulsive plot, she resurrects Cleopatra from the tomes of history, retelling the life of Egypt’s last pharaoh and vividly bringing Ancient Egypt to life. The novel also bears the hallmarks of El-Arifi’s message to attendees at the award’s ceremony – her version of Cleopatra is rebellion incarnate, a woman who refuses to be contained or pay heed to the barriers men and society attempt to put up against her.

The novel breathes fresh life into the historical retelling space that is saturated with Western mythology. Here is the voice of a woman too long claimed by historians and playwrights and reinstated here with the full force of El-Arifi’s ferocious prose. But El-Arifi “approached it like a memoir”, not a retelling. “Like all stories, history has a narrative and it is always political. From the form it takes to the words being used, it’s impossible to escape the author’s point of view. Memory, however, is ours. It is the purest truth we have, so I was really inspired by this concept of the novel being Cleopatra’s memoir.” It is “the only truth I could give her”, she adds.

The novel opens with the death of Cleopatra’s father, Ptolemy XII, and she is swiftly crowned the new pharaoh. Cleopatra’s life and reign spool forth from this point as she battles court politics and deadly sibling rivalries to keep her throne and turn Alexandria into a thriving city. Yet there is another city Cleopatra must be concerned with – Rome. To protect against mutiny, Cleopatra makes a deal with Julius Caesar – his troops for Egypt’s money – and the die is cast. The young pharaoh grows into a politically savvy, compassionate and often ruthless ruler, but her entanglement with Rome sets in motion a tragic collision between the two empires that will echo through the millennia.

Memory is ours. It is the purest truth we have, so I was really inspired by this concept of the novel being Cleopatra’s memoir. [It is] the only truth I could give her.

Very little is known for certain about the historical figure, Cleopatra. In her author’s note, which will be included in the published novel, El-Arifi writes: “The historians we have relied upon to tell her tale lived centuries after her death… The men whose words were preserved, such as Cicero, often originated from Rome, and their opinions were shaped by the propaganda of the Roman Republic. Her legend is only referenced in relation to Antonius and Caesar; too significant to ignore, too unpalatable to warrant her own narrative.”

El-Arifi set out to “reclaim” Cleopatra from these tales. The novel is divided into three parts, each named after a different archetype that has come to define the Pharaoh: witch, whore and villain. “The archetypes are built on her relationships to men. She is a witch because she bewitched men, she was a whore because she seduced them… I wanted to dismantle that truth. She was beyond that: she was a scholar, she was a mother, she was a friend. Who was she in relation to other things but men?”

In 2021, El-Arifi began a master’s degree in African Studies and her thesis – titled Between Rapture and Rupture: Cleopatra as a Site of Resistance for Black Women – set out to connect the life of a woman from ancient antiquity to modern Black womanhood. When writing her dissertation, El-Arifi previously explained that “the question was never, is Cleopatra Black?… The question instead was: why do I, a Black queer woman, have such an affinity to her myth?” The novel sets out with a similar, exploratory goal. Constructing the story like a memoir means that Cleopatra’s voice is not tied to the time at which the events are taking place. The effect is striking. Vacillating between the present and past, Cleopatra often addresses the reader directly – apologising for deviations in the narrative or challenging and lamenting the myths and stories that have circulated about her life. “It’s a conversation between Cleopatra and the reader,” explains El-Arifi. “It’s a conversation between Cleopatra and her histories.”

Continues…

In the final third of the novel, Cleopatra is confronted with one of the stories being spun by Rome to discredit her rule. “That’s the thing about stories,” El-Arifi writes. “You must know the story of the storyteller.” When I turn this on El-Arifi – what should readers know about her story in relation to the one she tells about Cleopatra? – the answer is moving. “I was othered in a way that I can imagine she was othered when she went to Rome.” She adds later: “I was raised in the United Arab Emirates to Arab and African parents, but was still taught the British curriculum. I had a British passport, I believed that was enough to make me British, but then I moved here and realised that many people need only look at me to decide I was not.”

During her research for the novel, El-Arifi became a mother, which “hugely impacted the way I wrote Cleopatra, sometimes subconsciously”. When Cleopatra’s son is pricked by a needle, it was “only in editing” that El-Arifi “realise[d] I had recounted my own horror at experiencing that with my baby’s first vaccinations”. It is “fascinating how many life experiences come out in my writing subconsciously”, she continues. El-Arifi, who lost her father at a young age, did not realise until someone pointed it out that every main character she has written always loses their father. Even Cleopatra’s father dies – a historical fact rather than a narrative choice – and she “lingers on her grief”, shaping her reign in counterpoint to his.

El-Arifi is a joy to chat to, a joy mirrored in her resplendent jumper, and her answers are incisive and reflective. This is the book she has been waiting to write. Thematically, Cleopatra sits alongside El-Arifi’s oeuvre in its exploration of race, womanhood, sexuality and agency, but it is also “totally different”. All her novels sit close to her heart, but “Cleopatra is a part of my soul… I’m so proud of it”. By giving Cleopatra a voice that defies the historical interpretations and mythologies that have sought to define her, El-Arifi makes a statement about the multiplicity of womanhood. “Look within and you will see me,” Cleopatra intones. “Witch. Whore. Villain. But I am also Cleopatra; the mother, the lover, the friend, and so much more. I am abundant.”