You are viewing your 1 free article this month.

Sign in to make the most of your access to expert book trade coverage.

‘This should be a wake-up call’: trade responds to inclusive organisations closing

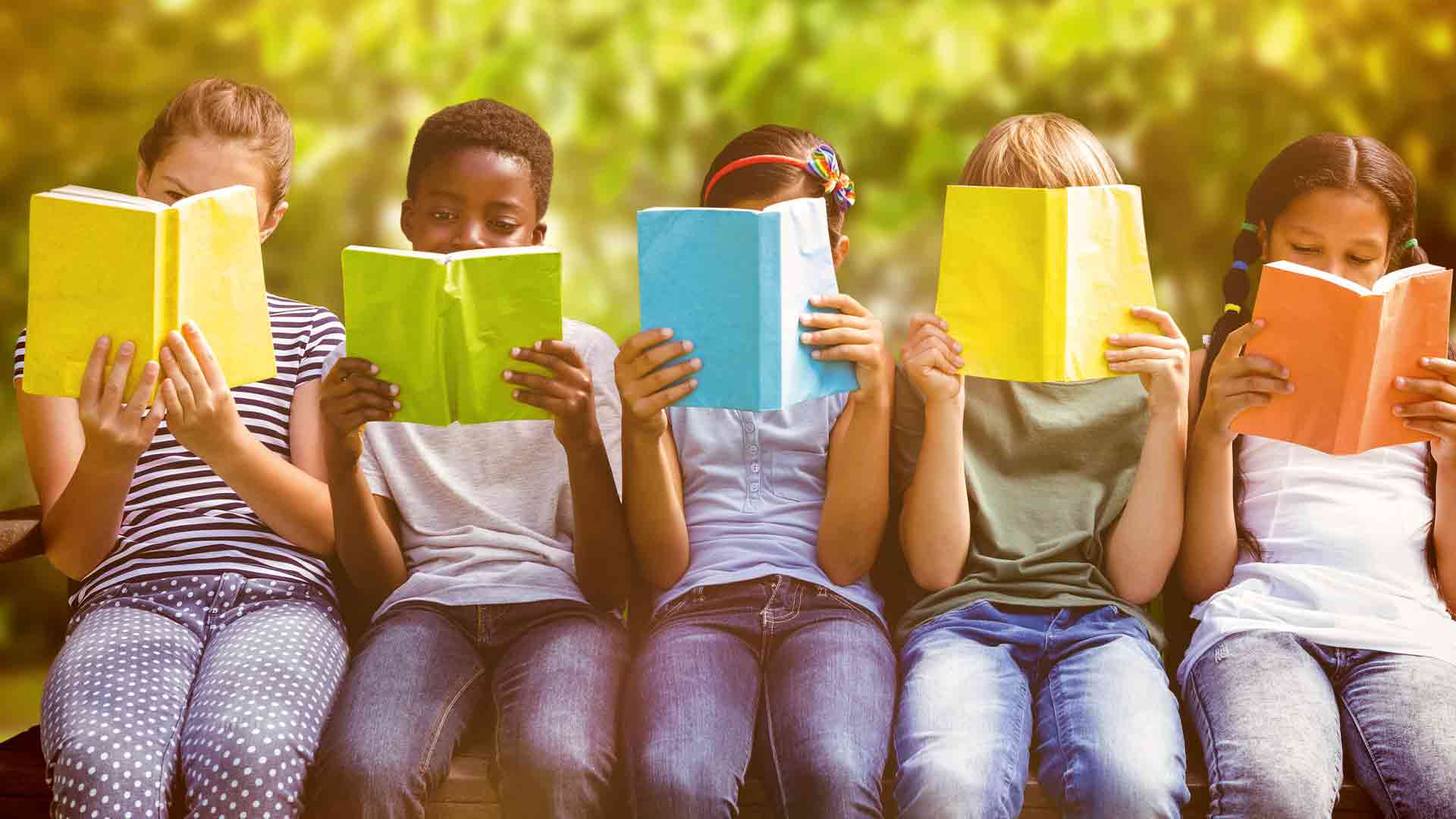

Trade figures have called on the publishing industry to ‘safeguard the future of inclusive storytelling’ following this year’s closure of several organisations championing representation in children’s books.

Last month, The Bookseller revealed that award-winning inclusive children’s publisher Knights Of was going into liquidation, following news earlier this year about non-profit children’s literature agency Pop Up Projects and inclusive kids’ press Tiny Owl shutting down. The Good Literary Agency, a social enterprise agency for British writers from under-represented backgrounds, also announced it was winding down at the start of 2025, with co-founders Julia Kingsford and Nikesh Shukla warning of a “stalling across the industry’s diversity and inclusion journey”.

At the same time, research has highlighted a decrease in representative children’s books. Literacy charity Inclusive Books for Children recently published a report revealing that only 6% of books published in 2024 for readers aged one to nine-years-old featured marginalised main characters, and just under half of those were by marginalised creators.

According to Selina Brown, children’s author and founder of the Black British Book Festival (BBBF), the link between this decline and that of inclusive publishing organisations is not coincidental. She says: “These organisations were the bridges connecting marginalised creators to mainstream publishing, and those bridges are now disappearing in real time.

The result is fewer stories making it through, and fewer children seeing themselves reflected on the page, at a time when the global majority in the UK is growing.”

Farrah Serroukh, who leads the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education’s annual Reflecting Realities report into ethnic representation in children’s literature, agrees: “There probably is a risk that we will regress in terms of volume and variation of representative output… With fewer players in the space driving that campaign and embodying those principles, it means that there are fewer people who are driving that kind of output. That doesn’t mean to say that bigger houses aren’t doing that work… but there is less consistency in larger houses.”

Co-founder of Tiny Owl Publishing, Delaram Ghanimifard, also emphasises the importance of smaller players. “These were not just publishers,they were change-makers. Without them, the industry risks losing the momentum that made children’s books more reflective of the world we live in. If it wasn’t for the constant pressure and example set by independent publishers, larger houses would never have moved towards diverse creators and inclusive stories. We are still at the beginning of that journey and losing these voices will set us back.” She adds: “Real change needs courage and persistence. These are the very qualities that small publishers brought to the table.”

Recently, a collective of independent publishing houses penned an open letter to the trade about the “existential crisis” they are currently facing. Jasmine Richards, founder of inclusive children’s fiction studio and publisher Storymix, believes the challenge is even greater for inclusive organisations, sharing: “It feels like every indie is struggling right now, but those led by people of colour or rooted in the business of equity start the race uphill. There is less cushion for them, no safety nets, and they face higher emotional and financial costs for the same work.

“When these presses disappear, we’re not just losing businesses, we’re losing the fertile ground of experimentation and incubation – the places where new voices, formats and audiences are discovered. Without them, the whole ecosystem becomes less imaginative and less able to reach readers.”

Ghanimifard concurs: “The small, independent publishers who led the way in championing inclusion have faced years of financial strain, made worse by shrinking budgets and rising costs. Their work depends on belief and commitment, not on profit margins – and that model has become increasingly unsustainable.” Brown calls grassroots publishers “vital”, expanding: “They’re the heartbeat of the industry, and they need funding, investment and real support to build sustainability.”

She believes that the closure of these organisations is a reflection of “a system that hasn’t yet adapted to support the very change it says it values”, adding: “For years, we’ve all been talking about inclusion, but the structures, investment and infrastructure needed to make it sustainable just haven’t kept pace… Many small organisations operate on shoestring budgets and keep things going through passion and purpose. But passion alone isn’t enough… If we want lasting impact, the whole industry has to reimagine how it nurtures and funds diversity from the ground up.”

If we want lasting impact, the whole industry has to reimagine how it nurtures and funds diversity from the ground up

Recently, BBBF launched a new publishing collaboration with the festival’s headline sponsor, Pan Macmillan. Brown says the venture came out of an ongoing conversation about “legacy, sustainability and changing the face of publishing for good”. She adds: “The festival had already built a vibrant community of readers and writers, and Pan Macmillan brought the global reach and infrastructure to match that energy. Together, we saw the potential to create something transformative – not just another imprint, but a new blueprint for publishing that puts community at the heart of the process.”

Meanwhile, Pop Up Projects’ founder-director Dylan Calder draws attention to “the scale of investment” that children’s literature organisations and indie presses are making in the wider book trade, which he feels “goes largely unacknowledged by the publishing community”. While Pop Up benefited from publisher contributions, Calder points out that such investment is “not strategic or cohesive, and it’s not done in recognition of the true economic value and impact those ventures are bringing to publishers’ cultures, business, products or customer bases”.

He continues: “It’s extraordinary, and heartbreaking, that the Big Five let Knights Of go. Someone could have stepped in and rescued the most important black-led children’s publisher of our time, and they chose not to. And this is going to keep happening – non-profit and ‘outsider’ ventures in children’s publishing will keep failing because while there’s a simultaneous crisis in public funding and a much-hoped-for Labour government that has offered absolutely nothing to the cultural sector, there’s a resounding silence in the industry.”

When approached by The Bookseller about the recent shuttering of inclusive children’s book companies, Publishers Association (PA) CEO Dan Conway said: “It’s sad to see the closure of these organisations which have played a positive role in the children’s books landscape. They leave a legacy in the authors, illustrators and designers who have been afforded their first opportunities in publishing by them and who have gone on to make successful careers in this space.” He added that children’s publishers “are dedicated to increasing the diversity of their books and this remains a key stream of our work in the Children’s Publishers Group”.

But Brown and Calder are urging industry leaders to do more. Brown says: “We’re witnessing the slow erosion of vital parts of the UK’s cultural infrastructure that have championed diverse voices for years. Without them, we’re already sliding backwards, losing momentum, losing talent and losing trust from communities who finally felt seen. “This isn’t only about business closures; it’s about the disappearance of safe spaces for creativity, belonging and truth-telling. I call upon Arts Council England, the Department for Digital, Culture, Media & Sport and the PA to urgently review this major crisis and work with us to safeguard the future of inclusive storytelling in the UK. Action must be taken now, not later, because by the time we call it a crisis, it may already be too late.”

Calder believes the industry should convene an enquiry via a body such as the PA to explore “the economic and legacy impact” of children’s literature initiatives and indie publishers. He states: “I think it’s time the publishing industry comes together for a collective conversation around the investment they need to make, and the collective power and advocacy they can bring, to better support the diverse ecosystem that nourishes them. Because without Pop Up and Pathways, Knights Of and The Good Agency, and all the other pioneering, diversity-forward initiatives hovering on the brink, publishing will become less diverse, not more.”

Ghanimifard points out that these closures come “at a time when racism, division and intolerance are visibly on the rise across the world”. She comments: “The publishing industry has a crucial role to play in countering that by fostering empathy, understanding and representation through stories… This should be a wake-up call. Inclusivity in publishing isn’t a trend to be managed, it’s a responsibility to be shared. The loss of these organisations leaves a gap that we can’t afford to ignore.”