You are viewing your 1 free article this month.

Sign in to make the most of your access to expert book trade coverage.

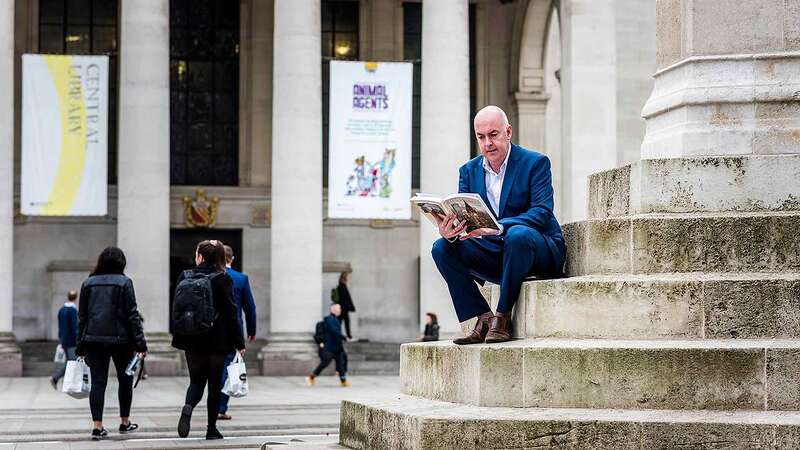

The Reading Agency founder urges the trade to reconsider what reading looks like

In April 2025, UK charity The Reading Agency released research pointing to “a growing reading crisis”. According to its State of the Nation in Adult Reading 2025 report, nearly half (46%) of UK adults struggle to focus on reading due to distractions around them – a figure that rises to over half of those surveyed aged from 16 to 44.

The number of UK adults who said they read regularly has dropped to 53%, down from 58% in 2015, and almost a third (31%) of adults said they struggle to finish what they start reading. Similarly, research by HarperCollins UK has found that fewer than half of parents of children up to 13 years old say reading aloud to children is “fun for me,” with almost one in three (29%) children aged five to 13 saying they think reading is “more a subject to learn than a fun thing to do”.

“All of the data, all of the evidence, is telling us that we’re facing a national reading crisis,” Debbie Hicks, founder and creative director of The Reading Agency, tells The Bookseller. “There’s a stark decline in reading engagement, and all the evidence shows that reading is absolutely a determinant of a happy, healthy and prosperous life.”

There’s a stark decline in reading engagement, and all the evidence shows that reading is absolutely a determinant of a happy, healthy and prosperous life.

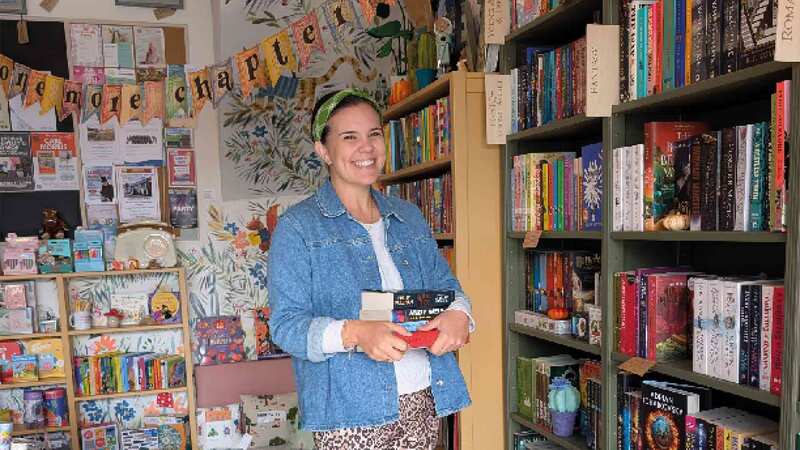

It is an urgent issue familiar to anyone in the publishing ecosystem, from publishers to librarians and booksellers – and indeed the government, which has launched the National Year of Reading 2026 with the National Literacy Trust as a “national mission”. Hicks is hopeful this collective effort will shift the dial, but says an industry and society-wide interrogation of what reading actually is, is needed to effect real, lasting change that reflects the world we are living in. To tackle a “reading crisis”, she says, we must all look at what we mean by reading in the first place.

“I think if you redefine what reading means, maybe there isn’t a reading crisis,” she posits. “Because I think the problem is that the definitions we’re using to classify readers are of a different age.” Far from minimising the problem, Hicks believes a wider understanding of what reading is – and can be – will offer a more comprehensive picture and enable more people to see themselves as readers. “I do get a bit frustrated about the ‘reading crisis mantra’, because I think part of it is just that we are labouring old definitions that don’t apply now. If you ask somebody if they’re a reader, and they listen to audiobooks, or they play video games or they read comics, they’d probably say no.”

Continues…

She sees the year of reading as an opportunity to “connect the dots between all the different players”. “I feel really strongly that to create a society of readers, we have to connect the dots in the reading ecosystem. We have to get the publishers, the booksellers, the libraries, the communities and the families all working together in an integrated reading ecosystem. Because nobody can do it on their own, but working together we can. I think the National Year of Reading will be a real opportunity to bring communities, families and the book industry together to work together around really addressing what it means to be a reader, and I think getting rid of some of those cultural stigmas around reading.

“It doesn’t matter how you get the content, does it? It’s the content that changes lives. I think interest pathways into reading are really important. It’s about meeting people where they are. And if you’re not a reader, giving somebody a book and expecting them to read, that is just not going to work. It’s about incentivising, motivating, encouraging.”

For Hicks, it is about making it clear that “it doesn’t have to be the classics” and that, while “the screen is very often seen as the enemy, quite often it can be a new way of interfacing with content”. “We need to get rid of that hierarchy around what people read and how they read,” she says, adding that, for her, “the adult piece is the most important piece” because “there’s an infrastructure to support children’s reading, but there isn’t an infrastructure around adults. So libraries are that place and they can play a hugely important role in getting adults reading.”

Ultimately, she says: “Reading is probably the wrong term. It’s actually engaging with meaningful content that’s important. In a way, it doesn’t matter how you do that, and so I think there’s a really big job we have on our hands about redefining what it means to be a reader.”