You are viewing your 1 free article this month.

Sign in to make the most of your access to expert book trade coverage.

Beyond Lunar New Year: why riding the global ESEA wave is a must

From KPop Demon Hunters to The White Lotus season three, set in Thailand, East and Southeast Asian (ESEA) stories dominate pop culture – and British consumers cannot get enough. In 2019, 10 books by ESEA authors appeared in the UK top 2,000. By 2024, that number rose to 18. Butter, Waterstones’ Book of the Year 2024, is a standout, demonstrating British readers’ appetites for ESEA literature. The book illustrates one of two opportunities for UK publishers: translation. The other is English-language books by diaspora authors that blend intersectional perspectives. Both are part of an ESEA wave surging around the globe.

For Pushkin Press editors Daniel Seton and Rory Williamson, the cultural origin of their translated fiction programmes is a selling point. “We it make a big deal that the books on my list are Japanese crime,” says Seton, whose covers feature Japanese script. Williamson’s short-fiction series employs striking covers by Jack Smyth that are evocative of ukiyo-e art. By foregrounding cultural authenticity with compelling narratives, Pushkin’s Japanese titles thrive in the UK and beyond.

Sinoist Books focuses on translated Chinese literature. According to marketing manager Daniel Li, fluency in Chinese gives his team an edge. “We often secure rights as the only bidder.” Employing editors who speak the language allows direct access to a rights pipeline from Chinese publishers. Li believes a prize like the Booker would be transformative for Chinese literature – just as Han Kang’s win for The Vegetarian boosted Korean fiction.

Sinoist’s approach is long-term: curate titles that will still matter for decades to come. The spotlight has long been on East Asia, but Southeast Asian voices are rising. Publishers like Major Books, which champions Vietnamese literature, are at the centre of a growing movement. This momentum is echoed by Anissa de Gomery, founder of FairyLoot, who seeks Thai narratives rooted in Southeast Asian mythology. “The Philippines is also on a rise,” she says.

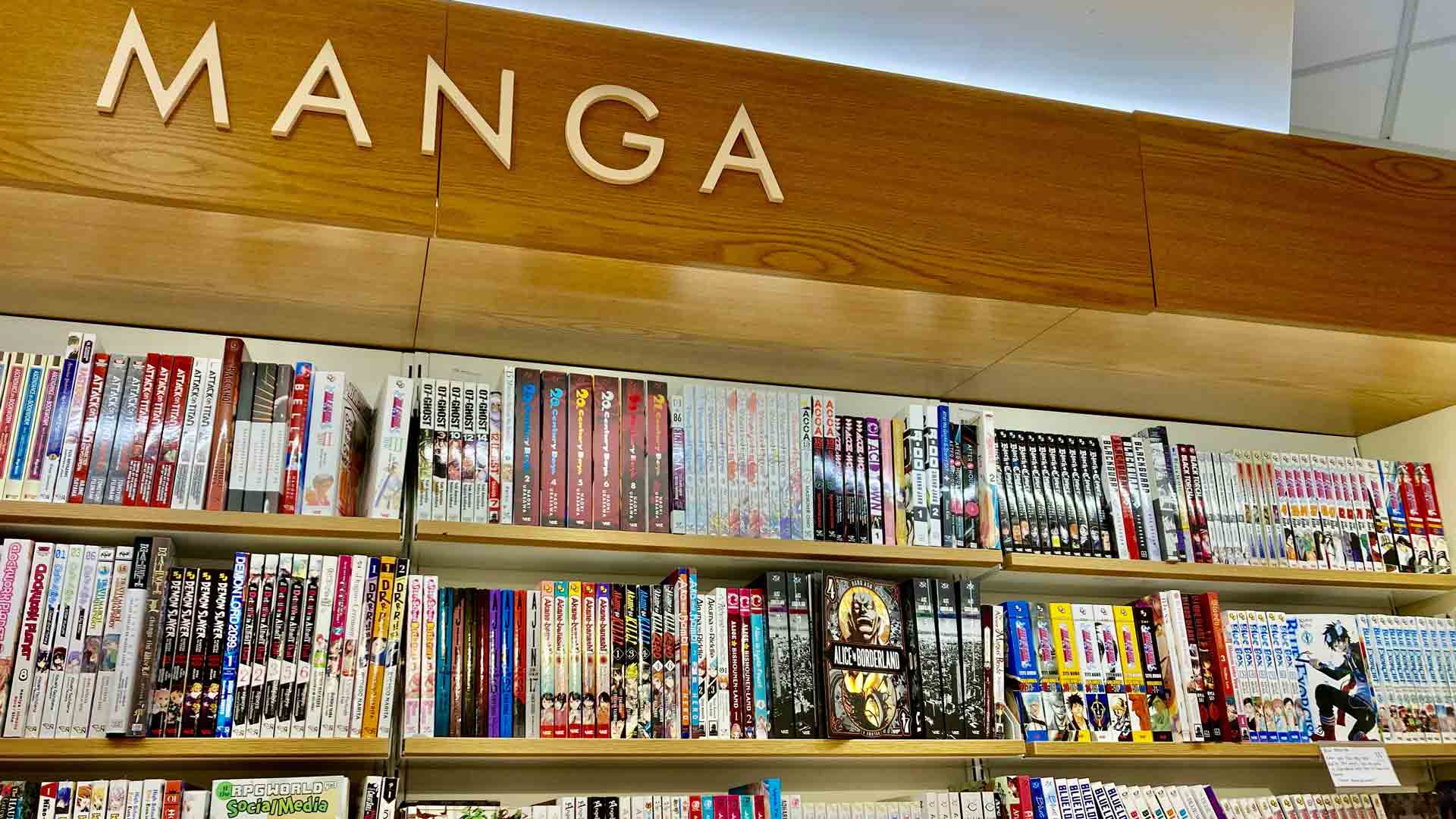

We must publish books kids want to read, not those we think they should read. Manga proves the point – the UK manga market is projected to grow nearly 25% by 2030

The Philippines was guest of honour at this year’s Frankfurt Book Fair – an accolade spotlighting a rich literary tradition. “Fantasy thrives on imagination,” De Gomery says, “and imagination isn’t limited to one culture.” Readers love ESEA stories for their originality and emotional depth. “It’s not hard to sell these books. Our subscribers celebrate them.”

Diaspora voices thrive in YA genre fiction, thanks to subscription boxes like FairyLoot and Illumicrate. Illumicrate founder Daphne Tonge credits Marie Lu’s Legend series as a breakthrough, inspiring a generation of ESEA readers and writers. For Tonge, quality is an imperative alongside representation: “I want the best fantasy book in every box,” she says – and many of these “best” books are written by authors from a vast array of backgrounds.

Founded by ESEA professionals, Illumicrate and FairyLoot have propelled the careers of chart-topping authors writing in English, including Eliza Chan, Thea Guanzon, Elizabeth Lim and Axie Oh.

Like subscription boxes, small presses are prioritising ESEA narratives. Emma Dai’an Wright, founder of The Emma Press, says: “I’m interested in the mixed experience – heritage, geography, identity.” Dai’an Wright explains that intersectional experiences shape books like Tiny Moons: A Year of Eating in Shanghai, a collection of essays about food and identity by Nina Mingya Powles, one of Emma Press’ bestsellers.

The momentum in adult titles is mirrored in children’s publishing, where ESEA creators have gained visibility. Recent releases include books by Emma Farrarons, Natelle Quek, Yu Rong, Emma Shevah and Lucy Tandon Copp, among many others.

Continues...

Do Re Mi Books, founded by Sam Voulters and Anna Watanabe, is bringing ESEA picture books to UK shelves. The debut list includes original works and translated classics never before published in English. Voulters and Watanabe are drawn to ESEA storytelling aesthetics. “Japanese picture books aren’t always logical or instructive,” says Watanabe. “They ignite imagination.”

The push for imaginative storytelling requires cultural sensitivity. Nghiem Ta, an art director at Walker Books, values authenticity. Finding suitable illustrators for ESEA picture books is not difficult. “I tend to search Instagram,” she notes, citing the global talent pool at every designer’s fingertips via social media. For Ta, illustrators with lived experience are invaluable: “They just get it. I don’t have to brief what goes on the table for Lunar New Year.”

Many ESEA children’s books highlight Lunar New Year or include moons to tie in with ESEA Heritage Month and the Mid-Autumn Festival in September. Dragons also dominate. Eight of Amazon’s top 20 ESEA Asian tales feature dragons. While these elements offer obvious marketing hooks, Farrah Serroukh, of the Centre for Literacy in Primary Education (CLPE), believes young readers deserve a broader offering that centres ESEA characters, despite the intrinsic value of such texts. Her research demonstrates that deeper, diverse acquisitions are necessary to engage readers and combat the reading crisis.

We must publish books kids want to read, not those we think they should read. Manga proves the point. The UK manga market is projected to grow nearly 25% by 2030, driven by middle-grade ESEA series like One Piece. Publishers cannot ignore this. Today’s young manga readers will be tomorrow’s adult consumers. They will seek out ESEA themes across genres.

As publishers diversify lists, discoverability is critical. Metadata matters, says EDItEUR’s Chris Saynor, who advocates richer Thema coding. But he emphasises that: “Thema isn’t about coding the author’s identity – it’s about subject content, which may well overlap.” Saynor urges publishers to avoid pigeonholing. For example, Maisie Chan’s Nate Yu’s Blast from the Past explores ESEA themes – but it is also about video games and... Atomic Kitten. Richer, relevant coding means more stocking options, better visibility and optimised marketing angles. Framing also matters. Sinoist’s Old Kiln by Jia Pingwa gained traction after a New York Times journalist linked its Cultural Revolution setting to the current US culture wars.

Alicia Liu, founder of consultancy Singing Grass Communications, says marketing should lead with universal stories: “Contextualise, don’t exoticise.” She urges publishers to attend international book fairs and contact specialist agents. “Gen Z and Millennials are already global in outlook,” she says. For Liu, the opportunity is simple: give readers what they want. Other media industries already do.

Jo Lusby, of Hong Kong-based agency Pixie B, calls for sustained engagement, not Lunar New Year tokenism. “Don’t treat ESEA books as seasonal,” she says, and warns against assuming ESEA books cannibalise each other: “Stories, themes and tensions differ vastly.” Tapping into themes beyond ethnic identity will drive sales.

From Pokémon to Labubu, ESEA cultural currents are shaping the mainstream tastes of readers. For UK publishers, the opportunity is clear: invest in ESEA stories. Look beyond Lunar New Year to harness the global ESEA wave.