You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

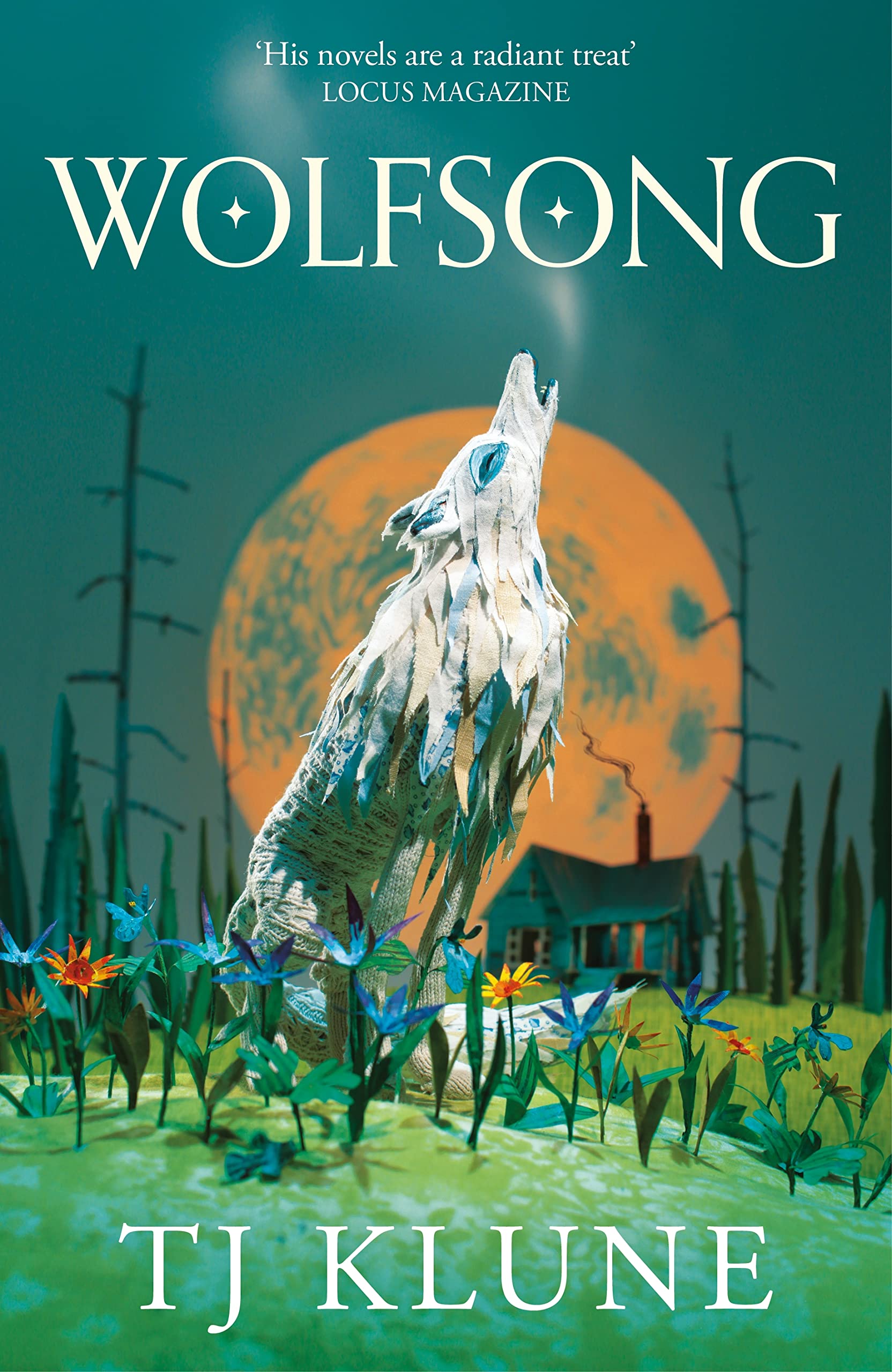

T J Klune discusses representation, queer characters and the power of happy endings

Fantasy author T J Klune uses the power of words to make entire communities feel visible.

"If there are queer characters in my books and they’re good characters, they will get their happy ending,” says American fantasy novelist T J Klune from his lightsaber-illuminated study in Virginia, US, when we speak over Zoom. “For too long queer people didn’t get happy endings in any form of media.”

Klune has devoted his writing career to creating positive depictions of queer characters and relationships, creating fantasy worlds where difference is celebrated, not condemned. “I think about all the books that I read when I was a kid; I never got to see myself,” Klune says, reflecting on the representational imbalance within fantasy he seeks to redress. His latest novel Wolfsong spans decades and marks the beginning of the Green Creek quartet. The novel follows Ox as his life becomes intertwined with the family who have moved into the house at the end of the lane—the Bennetts who, as it turns out, are werewolves. We follow Ox as he grows from a boy to a man, grappling with his father’s cruel legacy and his growing bond to the Bennett pack as he falls in love with the youngest son Joe. What happens next is a magical, heart-wrenching tale of danger, choosing your family, and unconditional love, as the Bennett pack and Ox are threatened by a rogue, maniacal werewolf and his followers.

Before he even knows what Joe is—he sees them as people he wants to know, as his friends, as his family

It is through Ox’s eyes that the reader understands how pigeonholing is incredibly damaging as he sees the Bennetts first as people and werewolves second. “He sees them as people,” Klune explains, “who have moved into the house at the end of the lane and when he starts to get to know them, before he even knows what they are—before he even knows what Joe is—he sees them as people he wants to know, as his friends, as his family.”

Creating space for reflection is not only characteristic of Klune’s plots but in the very act of his writing. “I don’t want queerness to be a plot point,” Klune says as we discuss the media’s portrayal of queer characters. I mention “Schitt’s Creek”, the award-winning comedy written by Dan and Eugene Levy set in a small American town following the Roses, a formerly rich family now living penniless in a motel. David Rose, played by Dan Levy, happens to be pansexual but the character’s sexuality never becomes the target of prejudice. Klune’s work reflects this ethos, building worlds where homophobia and discrimination against sexuality do not exist: “He [Levy] wanted to create a world where sexuality was never going to be the focal point of the story and that’s what I want to do with my books.”

Klune continues: “That’s what I love about shows like ‘Schitt’s Creek’ or ‘Our Flag Means Death’ or ‘Heartstopper’ that show that queerness is just a part of us. We are so much more than that one part. We don’t define other people by their sexuality, so why should we be defined by our sexuality?”

Klune avoids writing trauma that is overwrought. In Wolfsong, he combines action pieces with moments of calm. Although he professes his love of “dragons and heads getting lopped off with swords”, Klune stresses that the “moments where nothing needs to be fought and people are just sitting around enjoying each other’s company” are equally important. These “pinpricks of light” shine through dark moments, be it traditional Sunday dinner at the Bennetts’ or the walks Ox and Thomas, the leader of the pack, take through the woods. It is in these episodes where Ox and the reader come to understand the meaning of belonging: “‘What do you think pack means?’ ‘Family,’ I said promptly.”

You will continue with the story because you know, like I do, that these characters deserve the very best

Crying is inevitable and when I tell Klune I cried, he responds gleefully with, “While I don’t intentionally try to do that [make readers cry], when I go back and re-read over what I’ve written, I will cackle very evilly when I think, ‘Oh yeah this is gonna break so many hearts’.” Grief and trauma inform the events in Wolfsong but readers can always be assured that with Klune—despite the emotional rigour—there will be a happy ending. “You will continue with the story,” Klune says, “because you know, like I do, that these characters deserve the very best and they deserve the happy ending, though the road may be rocky to get there”.

Queer fantasy is changing traditional notions of the “hero” which Klune succinctly describes as “a straight white man with abs for days, big muscles and arm bands around their arms as they pose seductively with a sword hung behind their back”. Klune’s novels instead present everyday characters, with just a hint of fantastical, as heroic—Linus, the “40-year-old, fat, fussy queer man” in The House in the Cerulean Sea; Wallace, a success-driven lawyer-turned-ghost in Under the Whispering Door; and Ox, the human who can’t see his own worth yet runs with werewolves. Klune recognises the power of language, revels in it even, and is incredibly conscious of its deployment and its capability to effect change—“words have the power to make people happy, they have the power to make people sad”—and the author uses his words to make entire communities feel visible.

I hate writing sequels where I have to obey the rules that I made because it’s so hard!

Through the Green Creek series Klune will follow the Bennett pack, looking at a different romantic pairing in each instalment. Ironically, he admits his love/hate relationship with sequels, confessing that the second novel— Ravensong — was the hardest book he has written. The difficulty was abiding by the rules of his worldbuilding. “I love worldbuilding,” he despairs, “I love building. I love giving life to the characters and the world around them [but] I hate writing sequels where I have to obey the rules that I made because it’s so hard!” Yet, despite “hating writing sequels with a passion”, Klune felt compelled to do his characters justice. “By the time I finished [Wolfsong] I was like, ‘Oh my God, now I have to write more’ because I want to find out what happens,” he explains, “Then, when I finally sat down to start writing Ravensong, I was like, ‘There’s no way I can just stop after this one’.”

Wolfsong’s launch in the UK is a prelude to a busy period for Klune, with In the Lives of Puppets, a re-telling of Carlo Collodi’s The Adventures of Pinocchio, publishing in March 2023. Klune is clearly immensely proud of this novel, barely containing his smile when he tells me that it will ask the question, “Can you and should you show kindness to somebody who arguably doesn’t deserve it?” It will also feature, much to my delight, a “Roomba vacuum named Rambo”.

This isn’t even to mention Klune’s secret project. “Let me just say this summer we’ll be announcing some very cool news that I’m very excited about,” he teases, “some more books are coming your way.” Knowing Klune’s writing, we can be sure to expect more queer characters getting the happy endings long denied to them.