You are viewing your 1 free article this month.

Sign in to make the most of your access to expert book trade coverage.

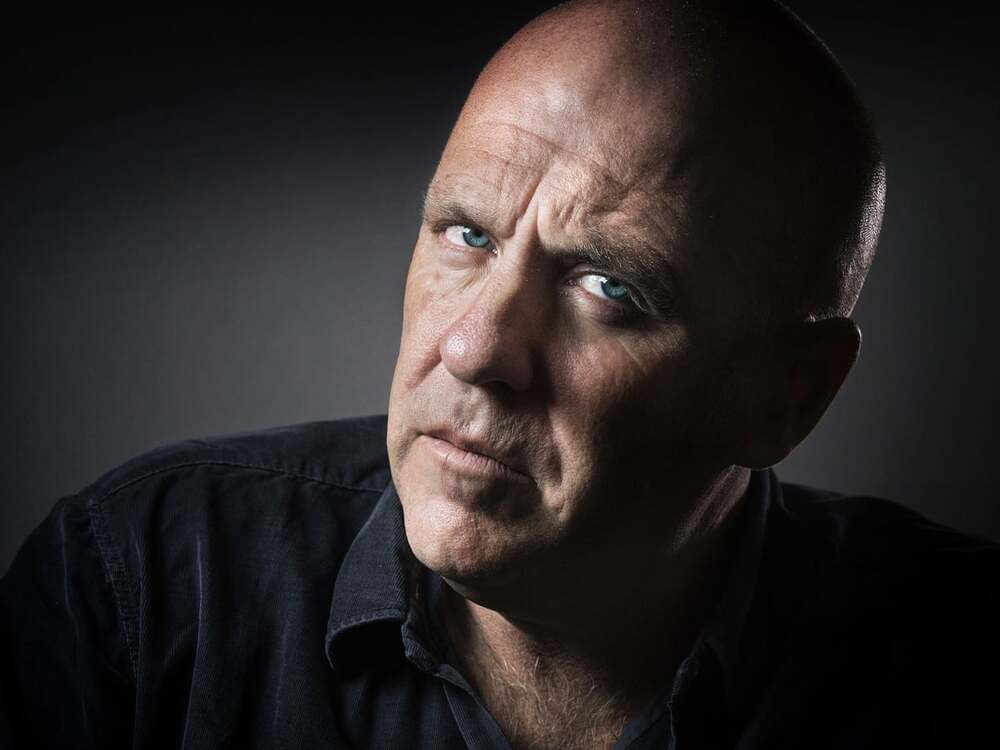

Richard Flanagan | 'We are many possibilities that masquerade as one. Literature reminds us of that'

When Australian novelist Richard Flanagan won the 2014 Man Booker Prize for The Narrow Road to the Deep North he made the startling admission that, straight after finishing the novel, he was so broke that he thought about working in the mines of Northern Australia.

But that novel’s huge success in the UK (in the week after the Booker was announced, more than 10,000 copies of the novel were sold, a 3,141% boost in volume week on week) and elsewhere (it was published in 40 languages), has meant that, happily for readers of serious literature everywhere, Flanagan has been able to continue as a novelist rather than becoming a miner. His new novel, published in November, poses questions about the nature of truth, lies and fiction.

First Person (Chatto & Windus) was inspired by Flanagan’s very first writing job back in 1991. He was a would-be author struggling to complete his first novel, when something very strange happened. Speaking over the phone from his home in Hobart, Tasmania, Flanagan recalls the moment: “This man, who was Australia’s greatest conman and a very famous corporate criminal, rang me at midnight to ask me if I would ghostwrite his memoir. It had to be written in six weeks and if I would do that, I would get AUS$10,000. I was labouring at the time and my wife was pregnant and we weren’t doing it easily. So I said yes.”

It’s said that reality has outstripped fiction but I don’t think that’s true. We need fiction more than ever to define reality afresh

The conman was John Friedrich, who was due to stand trial for an enormous multimillion-dollar fraud of the National Safety Council of Australia (NSCA). Three weeks into the writing process, and before he could appear in court, Friedrich committed suicide. Flanagan finished ghostwriting the book and it was published as Codename Iago: The Story of John Friedrich in 1991.

The unnerving episode stayed with Flanagan, and he found himself thinking about Friedrich long after the book came out. “I felt that he was a harbinger of the future in his solipsism, his derangement and in the sort of delirium that he created around himself.” Flannagan says now: “The delirium was something he invited people to be part of but once they accepted that, they no longer saw what the reality was.”

In the back of his mind, Flanagan realised it could form the basis of a novel. “It was such an extraordinary experience. He was the biggest corporate criminal; he stole about a billion dollars in today’s terms. He was enigmatic and he frightened me. He frightened me in a sense beyond the immediate physical fear I had around him at the time. He frightened me because I thought he spoke to some truth about the world, and I guess I wanted to write the book to try and circle that truth, to try and describe something of what it was that so terrified me.”

First Person takes the bones of Flanagan’s strange experience as its premise. In the early 1990s, Kif Kehlmann is a broke writer living in Tasmania with a three-year-old daughter and a wife who is pregnant with twins. He is trying, and failing, to write his first novel while not quite making ends meet through occasional labouring work. He has a wayward childhood friend, Ray, whose boss, the notorious conman and corporate criminal Siegfried Heidl, needs someone to ghostwrite his memoir in six weeks before he goes to trial for fraud to the tune of AUS$700m. Reluctantly, Kif takes the job, but soon comes to regret it.

The heart of the matter

Kif’s initial troubles stem from the fact that Heidl seems completely incapable of revealing anything at all about his life. He evades questions, goes off on tangents and frequently leaves the office that the publishing house has given the pair to work in, claiming to have to attend urgent meetings with his lawyer. But gradually, as Kif perseveres with the painful business of getting something, anything, on the page in order to hit his looming deadline, Heidl becomes a more menacing presence. Through Heidl’s endlessly changing stories, Kif starts to fear that the conman is somehow corrupting him. Is he ghostwriting a memoir, or is Heidl rewriting his future?

First Person begins with Kif working on Heidl’s memoir, and the novel itself takes the form of Kif’s memoir as he looks back from the vantage point of middle age. Flanagan is playing with the commonly held idea that a memoir is always the “real” story and somehow the “truth”. He thinks there has been a “loss of faith in the value of novels”, particularly in North America, “where there are people writing three volumes of memoir before they are 25. They are probably signing up ultrascans for six-figure deals at the moment,” he says, laughing.

“The nonsense of it is that we are not coherent or continuous beings. We are many possibilities that masquerade as one. Literature reminds us of that, and enables us to see that fundamental truth of the world. So I wanted to take the form of memoir to question it, to make people think about whether this world of the first person was actually a truthful world, or whether it was part of the delirium of the age and in fact what we needed were things that opened ourselves back up to the many possibilities of who we are and what we might be.”

Flanagan adds that he sees a connection between “these terrible epidemics of sadness and loneliness that seem to be blighting our society [and] this powerful idea that there’s only meaning to be found within yourself, not with others”.

Shifting narratives

As Kif grapples with getting Heidl’s story on the page, he finds himself adrift in a sea of alternative facts as the charismatic conman talks. In one sense it’s a situation that is currently being replayed in modern politics. But Flanagan doesn’t sound thrilled that life is imitating art. “There’s nothing worse than the zeitgeist novel and actually, in the final rewriting, I tried to tear away elements that were written years ago that might make it look like it was that sort of book, because nothing dooms a novel more than the pretence to immediate relevance. There was a joke about Trump that was in the novel two and half years ago - well, that had to go.”

First Person is also scathingly funny about the world of publishing as seen from the point of view of an unpublished writer. Heidl’s memoir has been commissioned by Gene Paley, a publisher who thinks only in terms of “the trade” and is in thrall to a celebrity author named Jez Dempster. It was whispered around the publishing house that Gene Paley was frightened of literature. And not without good reason. For one thing, it doesn’t sell. For another, it can fairly be said that it asks questions that it can’t answer.

Flanagan himself sees reading and writing as “one of the great transcendent private acts”, which “feel ever more subversive to me. Books begin to feel more and more like a new counter-culture. There seems a new power animating books that was absent for many years, and that has to do with the form. It’s said that reality has outstripped fiction but I don’t think that’s true. We need fiction more than ever to define reality afresh.

“Politics has collapsed as a place where questions can be asked. The media has largely collapsed and in that space, books remain to ask the questions. Even if they do it badly, they still do it.”

Photo © Joel Saget