You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

Helen Macdonald talks about her philosophical and symbiotic view of nature

Caroline Sanderson

Caroline SandersonCaroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

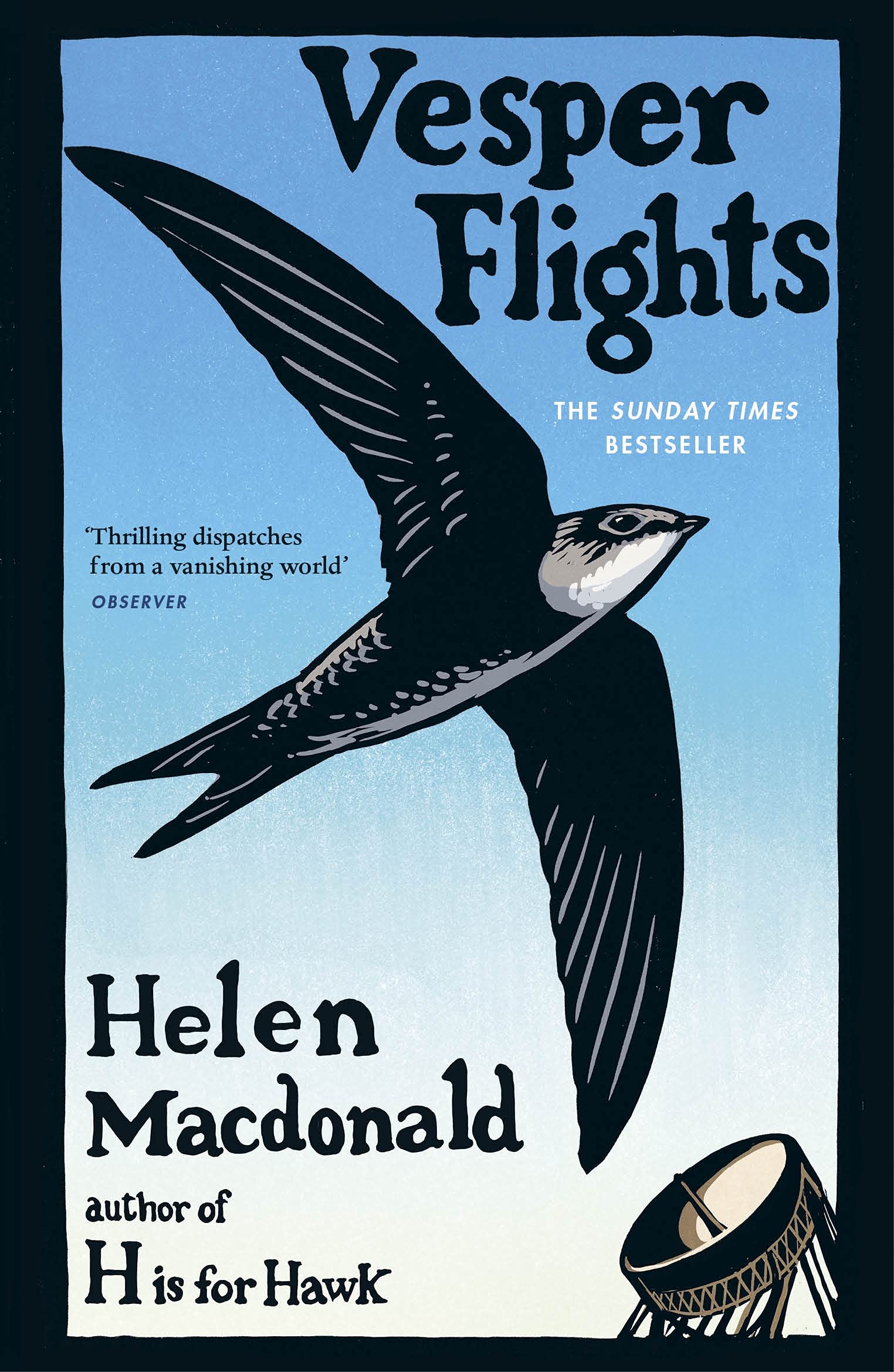

Helen Macdonald follows her acclaimed début with an eclectic anthology, one which is overtly political

Caroline Sanderson is a non-fiction writer, editor and books journalist. Her books include a travel narrative, A Rambling Fancy: in the F ...more

It’s six years, almost to the day, since I first interviewed Helen Macdonald. When we met in 2014, H is for Hawk, her memoir of goshawks and grief, had not yet been published, but reading it as a proof had already had a profound effect on me, mourning as I was the death of my own father six months earlier. Though books speak to us in individual ways, I felt sure at the time that H is for Hawk was something special. And indeed, subsequently published to enormous acclaim, the book went on to win numerous prizes, including the Samuel Johnson Prize for Non-Fiction and the Costa Book of the Year.

Six years on, its author was supposed to be on Midway Atoll in the Pacific Ocean, hanging out with albatrosses as part of her research for another future book. But the Covid-19 crisis means that instead Macdonald is at home with her Conure parrot, Birdoole, in what she describes as the “ridiculously chocolate-box” Suffolk village where she lives.

Within minutes of starting our Skype interview to talk about her new book, Vesper Flights: New and Collected Essays, she has me in fits of giggles with her description of the lockdown war she is waging against carpet moths. “They’re eating everything. I’m gently laughing at myself because—forget my ‘live and let live’ attitude—I’m shouting at them and squishing them against the walls. It’s really grim!” she laughs ruefully. And outside in her garden another battle is going on, between the house martins and blue tits for control of one of the nestboxes. “It’s like ‘Game of Thrones’. There has been a lot of backwards and forwards—for a few days the house martins have it, and then the blue tits take it back over again. It’s really stressful!”

I love the fact that the word ‘essay’ comes from the French essai, meaning ‘an attempt

Our human relationships with nature also form the central theme of Vesper Flights, a collection of 41 essays, some originally written as commissions for US magazines, some for the British media, others new for this book. “Compiling this collection was like making a quilt: it’s put together piecemeal from different things, but at the end feels like a continuous piece of material you can wrap yourself in,” Macdonald tells me. “I love the fact that the word ‘essay’ comes from the French essai, meaning ‘an attempt’, because when I start writing one, it always feels like a kind of puzzle; a way of working out something I’m thinking about.”

A varied flight

Taking in swifts (in her glorious title essay, equally gloriously illustrated in the jacket design by Chris Wormell), nests, glow-worms, the migration of birds over Manhattan, ants, hares, mushrooms and much more, the pieces in Vesper Flights are wonderfully diverse in tone and style, but almost all reflect on an aspect of how we interact with nature, and on its potential to instruct us. Every essay reminds me what a gifted writer Macdonald is: her prose is poetry but it also has a drenching kind of clarity. And this is good, because we shouldn’t enable ourselves to be lulled by the sheer pleasure of reading her. For these are urgent pieces designed to open our eyes to what she calls the world’s sixth great extinction.

Macdonald also reflected tangentially on similar issues in H is for Hawk, but Vesper Flights is, she says, a “much more political book. Really overtly so. I just think that times have changed and it’s really urgent now for me to speak out about climate change and political populism.” It feels a long way from the spider on the wall of her kitchen to such matters, but Macdonald uses her close observation of this creature as a salient example of why how we see animals matters. “This morning I looked at it for long moments and thought: ‘You know nothing of the wider world. Your world is all about the angle between the ceiling and the two walls and the egg case. And light and dark.’” So it’s about trying to imagine what it’s like to be another animal? “Yes! That’s just a good way of living one’s life, right? It’s how you should be thinking about every single person you meet. Imagining how the world is different for our fellow creatures is a kind of deep politeness, I think.” While we cannot possibly know what it is to be another animal, the attempt to imagine what it is like is, she says, is “good and important” because when we “rejoice in the complexity of things”, it ultimately leads to greater respect for all life.

Well of course, nature can be a solace. But many of the takes I’ve read seem symptomatic of our endless habit of feeling like we’re the only things in the universe, as if nature exists only for our benefit

Acknowledging that she writes from a position of privilege, Macdonald is nevertheless deeply concerned that class and economic deprivation shouldn’t be barriers to access and appreciation of the natural world. I tell her I was struck by her piece about bird-keeping entitled “Birds, Tabled”, in which she reflects on how our attitudes towards nature are shaped by history, class and power. “I’m glad you liked that essay because I really got interested in this notion of birds and animals in captivity, and what kinds of captive animals were considered acceptable and which weren’t,” she tells me. Further considering the relationship between natural history and national history elsewhere in the collection, she frames the annual “swan upping” census ritual, on the banks of the Thames, in the context of Brexit. And, at odds with the recent slew of books extolling the idea of the “nature cure”, Macdonald also professes her impatience with the argument that we should value natural places for their therapeutic powers.

I press her on this, given that getting outdoors amid all the flowering pomp of late spring is one of the things that is keeping me sane right now. “Well of course, nature can be a solace. But many of the takes I’ve read seem symptomatic of our endless habit of feeling like we’re the only things in the universe, as if nature exists only for our benefit. I think the notions that nature can heal us, and that coronavirus is a cure for the damage we’ve done to the planet, are particularly tone-deaf at the moment when the people who are suffering disproportionately from what’s going on are those with limited financial capital, living in crowded urban environments.”

Macdonald is routinely described as a nature writer, but this job title doesn’t seem nearly adequate to describe her deeply political and philosophical way of writing about the natural world. Still, while our conversation is necessarily serious at times, it is also full of delights. At one point, Birdoole—who has been shrieking from off-stage—appears on camera, resplendent in his feathery shades of green, blue, ochre and scarlet. Then Macdonald goes to the door to take delivery of a lockdown treat: some art materials. “I’ve realised that I really miss painting. I haven’t done it for two decades, but when I was a kid, all I did was paint.” She unwraps her fancy new paintbox in front of me and we coo over it for a while.

Extract

Science encourages us to reflect upon the size of our lives in relation to the vastness of the universe or the bewildering multitudes of microbes that exist inside our bodies. And it reveals to us a planet that is beautifully and insistently not human. It was science that taught me how the flights of tens of millions of migrating birds across Europe and Africa, lines on the map drawn in lines of feather and starlight and bone, are stranger and more astonishing than I could ever have imagined, for these creatures navigate by visualising the Earth’s magnetic field through detecting quantum entanglement taking place in the receptor cells of their eyes. What science does is what I would like more literature to do too: show us that we are living in an exquisitely complicated world that is not all about us. It does not belong to us alone. It never has done.

In her new book too, amid the politics, the urgency, and the desperate concern for the state of our planet in what Macdonald calls “these terrible times for the environment”, there is also much to spark joy. Vesper Flights is a cabinet of curiosities; a prose paintbox full of nature’s marvels. In Macdonald’s words: “Someone once told me that every writer has a subject that underlies everything they write... I choose to think that my subject is love; and most specifically love for the glittering world of non-human life around us.”