You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

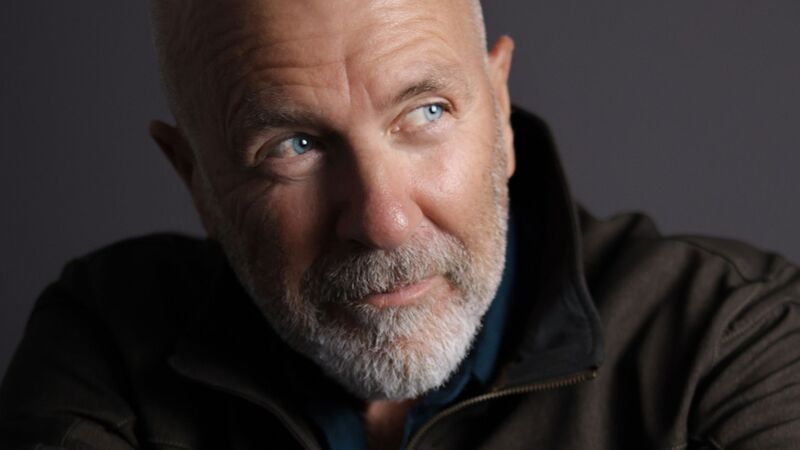

Emilie Pine on her debut novel and emotional honesty

Ruth Comerford

Ruth ComerfordRuth has been with The Bookseller for just over a year. She covers everything from the realities of independent bookselling today to F ...more

Emilie Pine, an academic and award-winning essayist, has followed her word-of-mouth hit Notes to Self with her first foray into fiction.

Ruth has been with The Bookseller for just over a year. She covers everything from the realities of independent bookselling today to F ...more

"It sounds quite flippant, but I just wanted it to sound like it does in my head,” says Emilie Pine about the narrative voice of her exquisite fiction début, Ruth & Pen. “When I wrote my essay collection, I didn’t know that was what my ‘voice’ was until somebody told me.”

Interior voices make up most of the telling of Pine’s novel, which follows two women, unknown to each other, over the course of a single day in Dublin in 2019. Ruth is in her mid-thirties, a successful therapist with her own practice, struggling with her infertility and her deteriorating marriage to Aidan, who is also grappling with unspoken hurt. Pen, a neurodiverse teenager, is preparing to attend a climate protest and trying to find the courage to tell her best friend, Alice, an important truth. What unfolds is a tender, quietly devastating story of two women struggling to find their place in the world.

I wanted to explore how difficult it is to put language on feelings that are so complex and ambiguous, and also to recognise the gap between the words and the feelings and experience

We see Ruth navigate a normal day with clients, gently probing them to articulate their problems, though she lacks the language to communicate with her own husband. As she gets ready to attend the protest, Pen steels herself by reflexively translating words into Latin, and collecting idioms “because they are more than the sum of their parts”.

Pine explains over Zoom: “I suppose I wanted to explore how difficult it is to put language on feelings that are so complex and ambiguous, and also to recognise the gap between the words and the feelings and experience.”

The two main characters meet twice—fleetingly—as they span the city, walking routes Pine mapped out during lockdown. “We couldn’t go more than two kilometres away from where we live, and a lot of it is set further away than that from me, so I had to get out an old-fashioned map and work out how the two would meet—it actually became a bit mental and turns out some of [the route] was wrong because Google maps had other ideas.”

Professor of Modern Drama at University College Dublin, Pine is also the author of award-winning essay collection Notes to Self (Hamish Hamilton) and several academic texts published by Palgrave Macmillan and Indiana University Press.

The collection—a series of personal, interlocking meditations spanning feminism, sexual violence and fertility—was a word-of-mouth indie hit that was seized by Hamish Hamilton editor Simon Prosser in a nine-way auction, after originally being published by feminist Irish indie Tramp Press. In many ways the novel grew out of Notes, Pine says.

“I had this extraordinary experience both writing and publishing the essays. The idea for the novel emerged out of conversations with Simon, but the motivation came from Notes. What I learnt from the process was manifold, but mainly to listen to what I really wanted to do.”

Taking time out

At a time when all roads in her career were pointing towards “big management-type projects”, Pine took a year off from her job, and began writing on 3rd January 2020.

“I’m very lucky to have had those career opportunities, but they weren’t me at all, and I’m obviously very fortunate to have the career structure that supports taking time off,” she hastens to add.

The author spent her early years in Dublin, before moving to London at 14. She returned to Ireland and accepted a place to read English at Trinity College Dublin.

“Can you tell I’m really into English?” she laughs, acknowledging the Emily Dickinson and Virginia Woolf references that pepper the novel. Her love of modernism led her to set most of the narrative in the minds of the characters over a 24-hour period, switching between Ruth and Pen and sometimes Aidan with each chapter.

“I really love the sense of intensity that comes out of compressing time, and what happens if you focus on the small. I wanted to show that over the course of one day, your life can change radically from one moment to the next—there are these moments when we say this is who I am and are really honest, both with other people and with ourselves, but those are really rare.”

Writing as yourself is not just about inner self expression, it’s a political decision to claim that voice

Pine heavily researched how sensory processing differences manifest for Pen’s character and also drew on her students’ experiences and those of a close friend’s children.

“I wanted to make it accurate, and like it was emerging from the character, and like it was part of [her] story rather than a set of traits. It’s strange to have novels without neurodiverse characters at this point.”

She also researched in vitro fertilisation for Ruth. “It felt very natural to write Ruth’s perspective and map out some of the issues I knew autobiographically,” she says, after writing about her own experience of infertility in Notes. “I didn’t want to do that again, but I wasn’t really done with the subject.” At the time of penning the novel, she was writer in residence at the National Maternity Hospital in Dublin, and felt compelled to convey some of the male perspective on an issue more traditionally centred on women.

“It became very apparent that fathers and second partners, whatever their gender, don’t get much of a look in, and aren’t really included in the fertility conversation."

Emotional honesty

Bodies, and their visceral processes, are central to the novel and Pine doesn’t shy away from the graphic honesty of certain bodily functions, something that was she lauded for in Notes.

“I wanted to continue that sort of emotional honesty in the novel, and so characters go to the toilet, because nobody seems to in novels. There’s a teenage girl masturbating because this is what bodies do, and putting them at the heart of narrative and making them features of narrative style is really, really important—there is blood, so let’s show the blood.”

But the decision to centre women’s bodies was also political for Pine, who has come to “distrust and dislike the pseudo-objectivity” of academic writing and the way she feels it seeks to alienate personal experience.

“I don’t know how many academic books I’ve read about the theatre and specific performances—but they never seem to talk about how uncomfortable the seats are, or that there’s someone coughing and it’s really annoying and you’re terrified you’re about to get Covid. The way in which we exclude subjective experience from this body of work that we revere in many ways, seems to me really false.”

She plans to continue her academic writing but says her style will be “very much changed” after writing a novel.

Extract

Ruth wakes with a full bladder, still half in a dream of being somewhere else. Where was it she had been, but no, work out where this is. Monday morning. Home. With the other side of the bed empty.

In the bathroom she flicks on the light, sits to pee, and automatically checks her underwear. No blood. Silent thanks. She will report this at the hospital later. All fine! Only a check-up! It’s not so easy to quell the fear though. Maybe she should go back to bed for a few last moments, it’s still early enough. But she has that sticky after-feeling of a feverish night. May as well shower.

She dips down to make sure the plug is out and there is a rush of dizziness, a clouding.

“Is this what you want?” he had asked last night, almost as they were hanging up. And Ruth had thought, what if I tell the truth? Perhaps, though, he wasn’t really asking. Perhaps he didn’t want to know the answer. She cannot, now, even remember his intonation. “Is this what you want?” Was it a question or an accusation?

“The shift away from [the academic style] first into the personal essay and then into fiction, is a very deliberate move, I think. Writing as yourself is not just about inner self expression, it’s a political decision to claim that voice as also a professional voice, and also a way of knowing the world, and also a way of writing knowledgeably, and with expertise.”

Metadata

Pub date: 05.05.2022

Imprint: Hamish Hamilton

Format: HB, e-book and audio

ISBN: 9780241393666 / 986257 / 573297

Rights: Dutch (Nieuw Amsterdam), German (btb/Random House Verlag) Italian (Rizzoli Editore), Polish (Cyranka), Swedish (Wahlstrom & Widstrand)

Editor: Simon Prosser

Agent: Karolina Sutton