You are viewing your 1 free article this month.

Sign in to make the most of your access to expert book trade coverage.

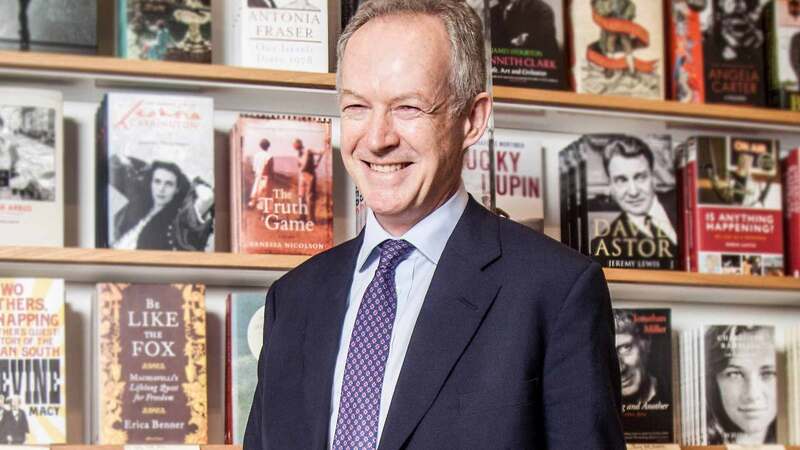

David Whitehouse | Publishing, when it works, has to be everyone having a small love affair with the same thing

David Whitehouse’s second novel, Mobile Library (Picador, January), is a book for bibliophiles; a modern fairytale of four people thrown together as a makeshift family who take to the road in a stolen mobile library. There is more to the novel than just a madcap road trip, though. Whitehouse plays with the traditional dark undercurrents of fairytales, alongside the novel’s humour and heart.

The protagonist is 12-year-old Bobby Nusku, who obsessively archives remnants of his mother as he waits for her to return. In the meantime, he has to deal with the mood swings and neglect of his father. He befriends fortysomething mobile-library cleaner Val and her disabled daughter Rosa, but when everything starts to go wrong, the trio take to the library and end up adding another traveller to their ranks, in the form of ex-soldier Joe.

Despite the undeniable and necessary appeal of Bobby, Whitehouse was keen to avoid stereotypes: “I hate precocious child characters, precocious anyone really. Bobby never felt precocious to me, he felt like more of a fantasist. He is trying to escape all the time from his awful life by disappearing into his own head or in his friendships. For me, it’s a much more interesting way of exploring adults and everything bad about adulthood through the na√Øve eyes of someone who hasn’t experienced it yet.”

When he was a child, Whitehouse’s mother was a cleaner in a mobile library. “When I was seven, it was like having my own Transformer, my own giant 40-ton babysitter with all the books in the world in it,” he says. “I’ve always been fascinated with the idea of the vehicle itself. It seemed quite a romantic way of having an adventure.”

Part of what prompts Val to commandeer the vehicle is the local council’s decision to reduce the mobile library service. Whitehouse says: “It seems to me that they’re the cure for any ailment. I firmly believe that most societal problems can be solved with a mixture of education and imagination, both of which you’ll find at the library—and yet we close them down. Politicians for decades have stood there and talked about education, but education needs a place that’s not just the classroom. If education solves everything and you take away education’s house—which is what the library is—what happens?”

As well as the literal library books that populate the novel, Whitehouse nods to several classic stories in his narrative, from Moby Dick to Matilda, Tom Sawyer to Gulliver’s Travels. One of Whitehouse’s aims with Mobile Library was to explore the idea of a children’s book for adults: “I want to write a translation of a children’s story. What if James and the Giant Peach was real? What if all of that happened, but in a book for adults, without magic?” Indeed, Mobile Library sees a boy who has been dealt such a raw deal by life (replace freak accidents and grotesque aunts with car accidents, alcoholism and neglect) that he escapes with a ragtag bunch of friends in a giant mobile library (peach).

A sleeper hit

Whitehouse’s first novel, Bed, was published by Canongate in 2011 after winning the inaugural To Hell with Prizes Award for unpublished novels. Canongate publishing director Francis Bickmore was a judge for the prize, but he actually passed the novel up when it was first sent out by Whitehouse’s agent, Cathryn Summerhayes at WME. As a result, Bickmore ended up paying significantly more for it after its win. Whitehouse can announce himself as the only winner of the award—despite Bed gaining critical success and winning the 2012 Betty Trask Prize, To Hell with Prizes was not revived for another year.

Whitehouse is, perhaps predictably given his experience, a big fan of literary awards: “Prizes are exciting, they make people talk about books. If books are on the news, that’s a good thing. It’s the same as the Turner Prize—every year there’s the same boring debate about what art is. Who gives a fuck? It exists and it’s making other people create stuff. Why would anyone not like a prize . . . that’s like not liking Christmas.”

In the face of criticism levied against book prizes for being elitist, Whitehouse argues that literary awards are not the place to fight that battle: “If we’re trying to combat elitism in the realm of very literary novels, then we’re probably wasting our time. If you’ve got a problem with elitism, it’s not best fought with the Booker. It’s best fought in everyday life, where middle-aged white men with Oxbridge educations are coming off better than other people. At least the people on the Booker list have gone and written a good book. These people have made something good, and that deserves rewarding.”

On the move

Mobile Library is undeniably a more commercial prospect than the experimental Bed. Whitehouse says: “The only conscious decision on my part was to show that I can tell a story in a more traditional sense. It was an exercise in more traditional storytelling, to prove to myself that I could do it. Bed’s not that at all, it’s all over the place . . . a kind of tightrope walk which occasionally falls off, I think. By proxy of it being a more traditionally told story, that probably makes it more commercial.”

Having said that, Whitehouse is not a fan of genre distinctions beyond those that help people find books they will enjoy: “It becomes more than genre, [it] becomes a type of person and it excludes people. That’s not the point. Telling a man on the street that a book is ‘literary’ or ‘commercial’ isn’t helping them find what they want—he would say: ‘Well actually I want something that’s sold a lot of copies.’

“I’ve walked in the door [at Picador] just after Jessie [Burton, author of The Miniaturist] and the only thing I’ve really ever said to them is to do exactly what they did with The Miniaturist. It’s a great story and she’s a great writer, but that’s magic. How does a book do that? How does everyone suddenly know about it—how is every bookseller talking about it?"

Whitehouse credits the publisher for its investment in its titles: “Everyone from the receptionist to Paul [Baggaley, publisher at Picador] to Anthony [Forbes Watson, m.d. at Pan Macmillan] is completely invested. Publishing, when it works, has to be everyone having a small love affair with the same thing. You can see that with The Miniaturist. That’s a group of people delivering something—not just Jessie, although she’s done the legwork. I imagine the quality of the biscuits at my launch will be significantly better because of her.”

Whitehouse endorses anything that makes books appealing and accessible, be it libraries, prizes or book bloggers. For Whitehouse, Mobile Library is “a book about family, love and escape—and books. I think if we’re going to try to make books important to everyone, stories should reflect that in some way.”

Metadata

Publication 15.01.15

Formats EB/HB (£14.99)

ISBN 9781447274728

Rights US (Scribner), Brazil, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Korea, Slovakia

Editor Francesca Main

Agent Cathryn Summerhayes, WME

CV

1981 Born in Nuneaton, Warwickshire

2002 Graduates from London College of Printing with a BA in Journalism

2006 Begins writing his debut novel, Bed

2010 Wins To Hell With Prizes Award for unpublished novels for the Bed manuscript

2011-2012 Bed published by Canongate; it wins the Betty Trask Prize 2012