You are viewing your 1 free article this month. Login to read more articles.

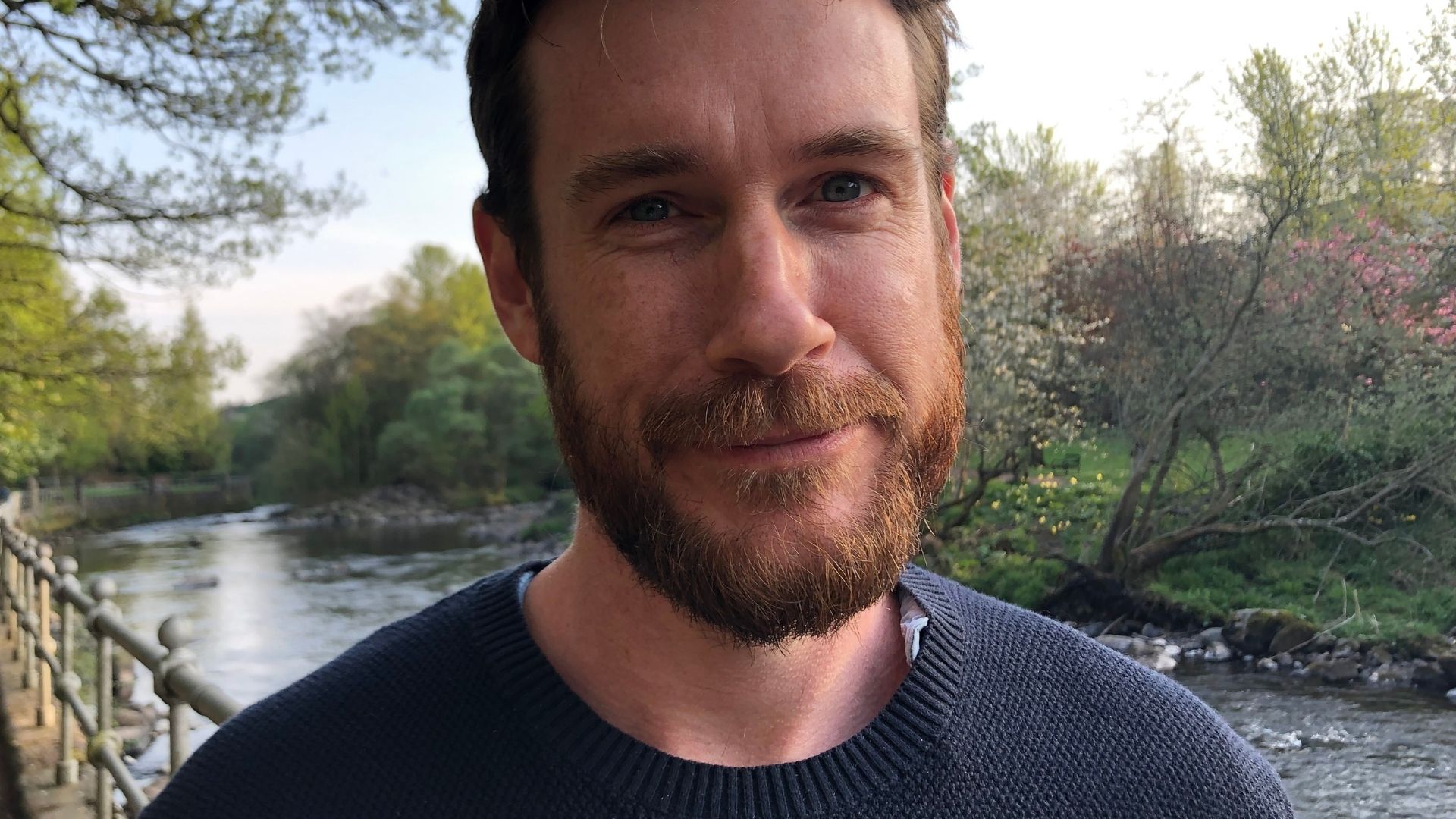

Malachy Tallack in conversation about our symbiosis with nature

The novelist and nature writer Malachy Tallack has written a book about fishing. But it is also an exploration of how the activity ties people to the landscape and gives them a sense of place.

There’s an old observation by the American comedian Steven Wright that “there is a fine line between fishing and just standing on the shore like an idiot”. When I quote this to Malachy Tallack he laughs and adds: “It’s more like a complete idiot."

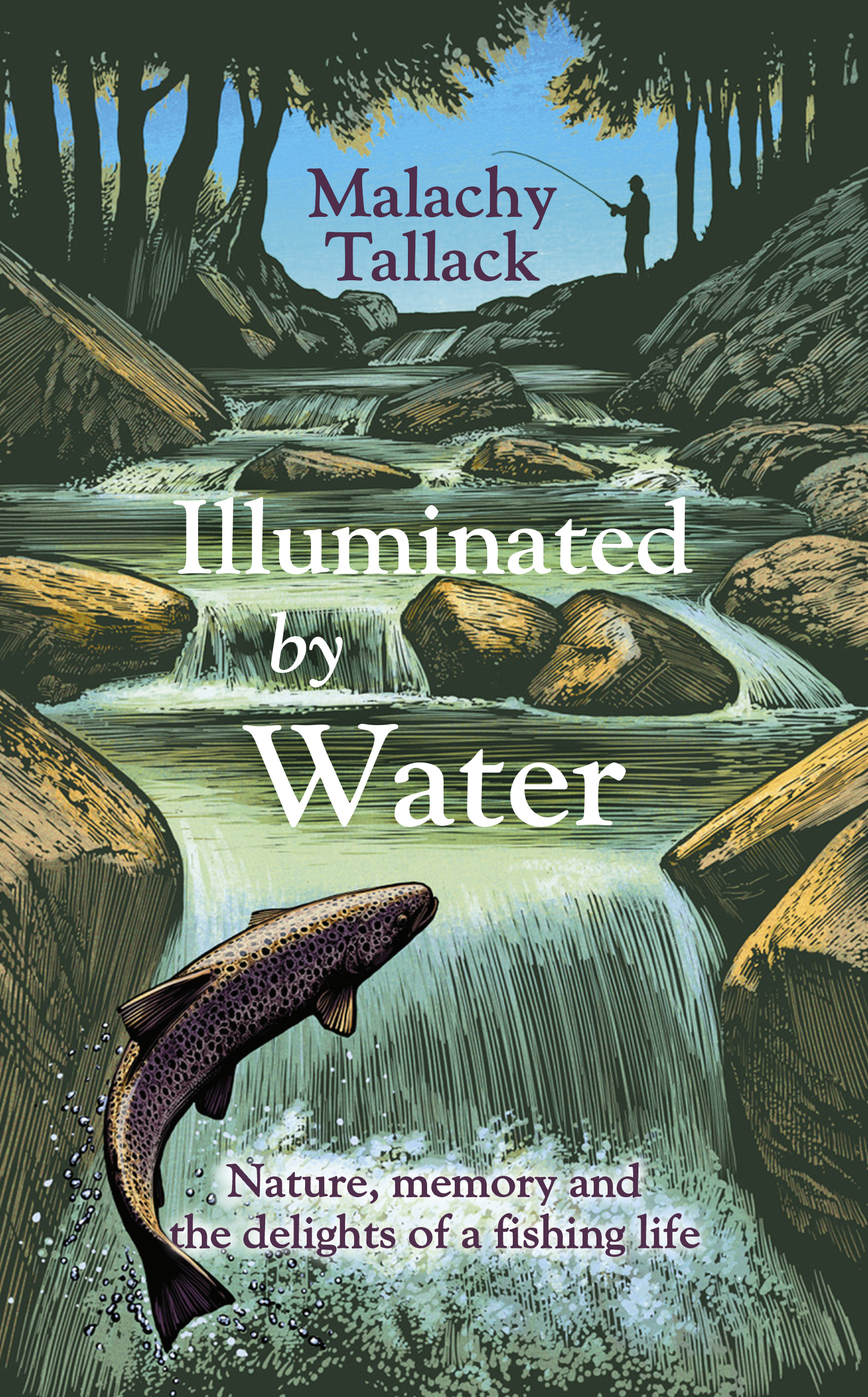

Which is a generous thing for the novelist-cum-nature and travel writer to say, as Tallack has just authored a whole book of linked essays/travelogues on fishing, Illuminated by Water (Doubleday). “Part of the appeal of writing about fishing for me is both that I enjoy it so much but also that it’s such a ridiculous thing to do,” he says. “It’s interesting because it is a complete waste of time, but such a complicated waste of time with this rich cultural history that’s been built around it."

“And the pleasure of it is interesting. Why do we find certain things joyful and exciting? What is it about standing on a riverbank for hours that can be so thrilling for so many people? I’d say that there are all kinds of levels and layers to this pleasure but one of them is about feeling connected to places. Now, lots of people write about connection to nature and engagement with place but with fishing you are being fairly still, quiet and are there for a long time. You experience a place in a way that you never would if you were just passing through and completely differently than any other activity.”

Illuminated by Water is centred around fishing and, sure, there is much to delight the hardcore angler. On the other hand, it does not matter if you don’t know a goldhead from an emerger (two different artificial flies, apparently) as in many ways the core of the book is a deep and wonderfully poetic meditation on how nature, landscape and place fit in with modern life.

I am conscious, at such times, of how remote any strict moral theory seems from the reality of that fish, of those guts, of that water

Tallack takes us on his fishing trips across the globe to places as far afield as New Zealand and Vancouver Island. They tend not to be fishing trips per se though, as Tallack happens to go fishing while visiting them. But the bulk of the book takes place in the lochs and canals of Scotland and England. There is some interesting social history here, too, for example that angling as a pastime was first an urban activity as a way for city people to get out at the weekends.

The thrill of learning

And it is part-memoir, too. Tallack’s “fishing origin story” began when he was eight in East Sussex and a friend of his parents—the moustachioed and pipe-smoking Paddy—took Tallack and his younger brother Rory to a lake at nearby Scaland Wood. He and his brother were obsessed from that afternoon and their mutual love of fishing would soon help the boys assimilate and cope with culture shock when the family moved to Shetland. But ever since, Tallack writes, he always goes back to that day: “Throughout my life I have been trying to retrieve something of that early encounter with wonder, that overwhelming feeling of excitement, of discovery, of possibility, of awe. Every time I pick up a fishing rod, even now, I am trying to go back to Scaland Wood to experience again the thrill of learning that the world can be coaxed into such glorious disclosure.”

I’ll always associate fishing with: freedom and youth

One of the most interesting chapters is Tallack’s look at the biggest disconnect from nature in modern life: the distance most people are from what they eat—and the repugnance or disdain of many at what it takes to get food to the table. Tallack is sometimes a catch-and-release sport angler but he also eats a lot of the fish he lands. And he reflects on this in an entertaining but challenging discourse which takes in a wide range of views from animal liberation theory to the philosophy of Peter Singer. But it always comes back, and must come back, to something very elemental: “These days, when I take a fish, I usually gut it straight away, holding it just above the water from which it came. The parts of the body for which I have no need are returned to that water. Something in there will have need of them, nothing will go to waste. What began as an act of convenience, of cleanliness, has become a way of giving back."

“I am conscious, at such times, of how remote any strict moral theory seems from the reality of that fish, of those guts, of that water. How fragile and inadequate our ethical codes appear when considered in the places to which they are supposed to apply.”

Though he was born in England and has lived on the Scottish mainland for some time (he currently resides in Dunblane), Shetland is where Tallack “still think[s] of when I think of home; it is still part of me. Maybe it is because growing up, we went from Sussex where it was really kind of constrained in the things we could do to this absolute freedom. As youngsters there was the sense that there was no risk from other people and we were allowed to go out and wander and go fishing. And it’s part of what I’ll always associate fishing with: freedom and youth.”

Throughout his twenties Tallack was a singer-songwriter, releasing four folk-rock albums and touring with the likes of King Creosote, Karine Polwart and Runrig. But he wrote stories and was a journalist all the while and gradually shifted to writing full-time. That included becoming the founding editor of the online journal the Island Review and editor of Shetland Life magazine. In a number of ways, Shetland underpins his books—across fiction and non-fiction—as they focus on islands and isolation. Sixty Degrees North (Polygon, 2015) is a travelogue to remote places around the globe in the high latitudes (Shetland’s main town, Lerwick, is at 60.15° N); The Un-Discovered Island (Polygon, 2016) is a compendium of mythical islands once believed to be real; and The Valley of the Centre of the World (Canongate, 2018) is his Shetland-set début novel revolving around the lives in a remote crofting community. He is currently working on his next novel for Canongate, meant to be published in 2023. “With luck it will be, but on some days it’s hard to believe,” he says.

Tallack adds: “Thinking about my books, I think I’ve been lucky in that Shetland has made me interested in place as experience and the way that place shapes individuals and shapes cultures.”