You are viewing your 1 free article this month.

Sign in to make the most of your access to expert book trade coverage.

Bologna Children’s Book Fair Guest of Honour Estonia: ‘Small voices’, big impact

The Baltic nation is in the spotlight at the 2025 Bologna Children’s Book Fair, with the relatively small country showcasing a punching-above-its-weight cohort of creatives.

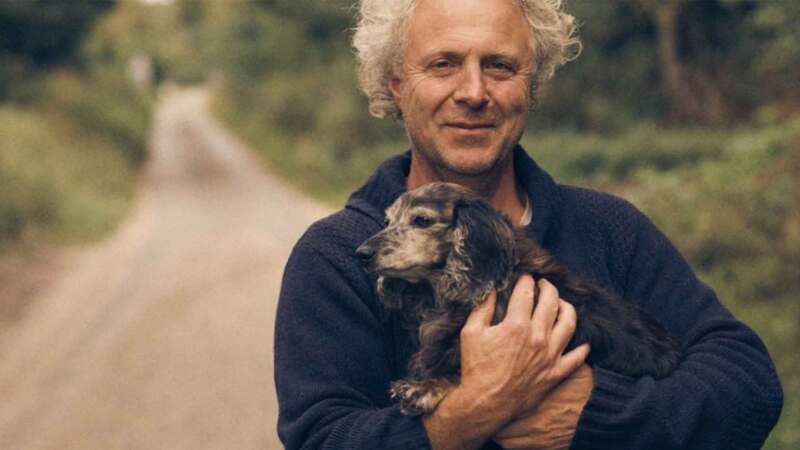

Tom Tivnan is the managing editor of The Bookseller.

When outlining her wishes for Estonia’s stint as Guest of Honour (GOH) at the 2025 Bologna Children’s Book Fair – and what happens long after exhibitors leave the Fiere – Ulla Saar, director of foreign relations at the Tallinn-based Estonian Children’s Literature Centre and one of the GOH committee organisers, says: “We hope to surprise the foreign publishers, agents and audience with the diversity of styles and topics we can offer. And of course, that a lot of the authors we cherish will find their way to foreign markets.”

Those from the Estonian kids’ sector are not coming out of the blue to the international trade, however. This, after all, is not Estonia’s first rodeo when it comes to being the centre of an international show; it was part of the Baltics Market Focus at the 2018 London Book Fair, though that turn was shared with neighbours Latvia and Lithuania, and was not focused solely on children’s. But there are a number of increasingly border-crossing children’s book creators from the country such as Triinu Laan, Reeli Reinaus, Tiina Laanem, Anti Saar, Marju Tammik and Anne Pikkov.

Continues...

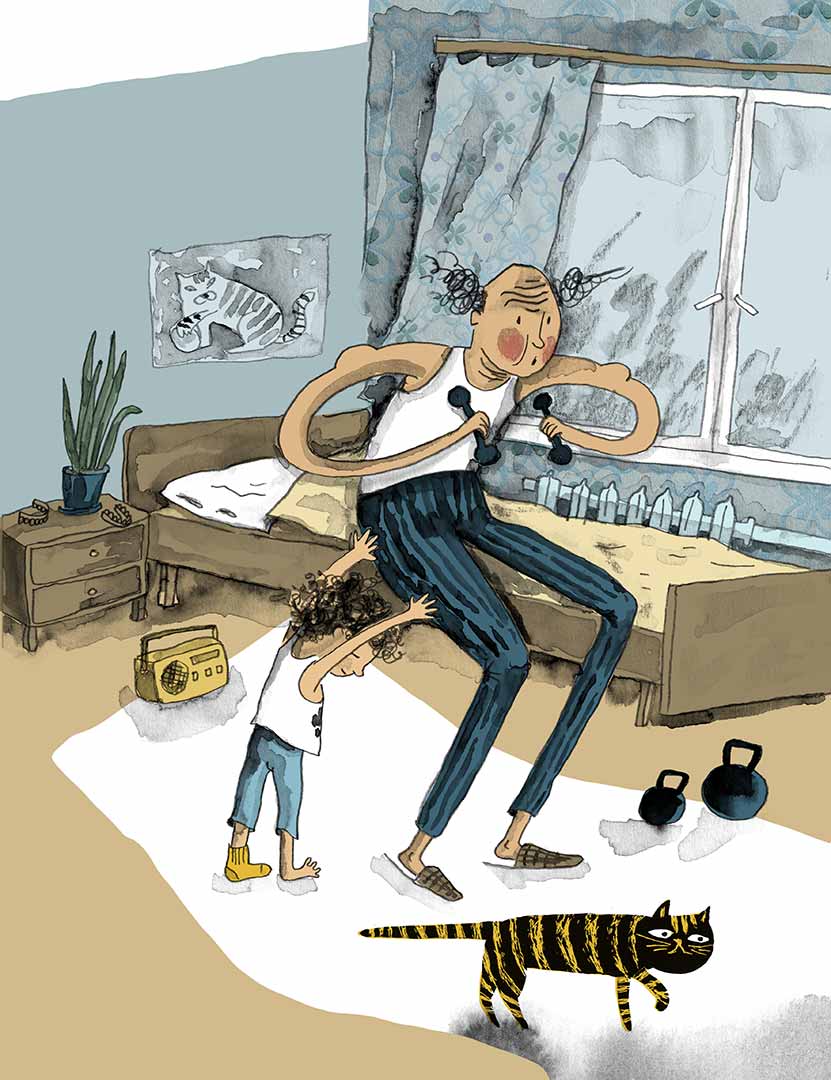

Laan and her frequent illustrator Marja-Liisa Plats have created one of Estonia’s biggest recent rights successes with Luukere Juhani juhtumised (John the Skeleton). The picture book has been sold into a dozen territories and picked up a number of gongs in the half-decade since its original Estonian publication, including the 2022 BCBF Illustrators Exhibition prize and this year’s Mildred L Batchelder Award for most outstanding children’s book translated into English and published in the US, in Andrew Cullen’s translation for Massachusetts-based indie Yonder.

Continues...

Children’s titles comprise roughly a quarter of the Estonian market’s circa €35m (£29.2m) annual sales. Just over 800 kids’ books were published in Estonia last year, 204 of which were original titles authored by Estonians. Saar points out: “That’s quite a large number considering our population of 1.4 million people, approximately 900,000 of whom read in Estonian.” (Russian is the second-biggest mother tongue in the country, spoken by about a quarter of the nation.) Given that relatively small size, Estonia has an amazingly thriving publishing scene, with a number of players no doubt familiar to exhibitors at this Bologna, such as Päike ja Pilv, Koolibri, Draakon & Kuu, Tammerraamat, Pegasus and Tänapäev.

Continues...

While a quarter of the country’s first language is Russian, it is no longer the dominant second tongue of ethnic Estonians, as just over half now speak English, a huge generational shift (in 2000, about a quarter of Estonians spoke English). This, however, dovetails with the industry’s recent hot-button issue of inexpensive English book exports threatening local-language publishing.

“It is a big problem in Estonia as well, especially in YA,” Saar says. “It’s the downside of globalisation. However, thanks to our history we have a really strong sense of, and pride in, our own language and reading in Estonian. Teachers, librarians and parents find it very important that children read in their native language.” Saar points out that schoolchildren annually must read at least 10 Estonian books and evaluate them. This “might be one of the reasons why Estonia is near the top of the PISA [Programme for International Student Assessment] tests in reading”.

And, Saar argues, this has helped feed into the vibrant Estonian children’s literature scene. Because of its size, Estonian authors and illustrators might not be that well known internationally, but this Bologna might just change that. Saar adds: “Small voices can sometimes be the most interesting ones.”