ADCI shortlistees reveal their writing motivations ahead of prize announcement

The three shortlisted authors of the third annual Authors with Disabilities and Chronic Illnesses Literary Prize talk representation and their paths to publication.

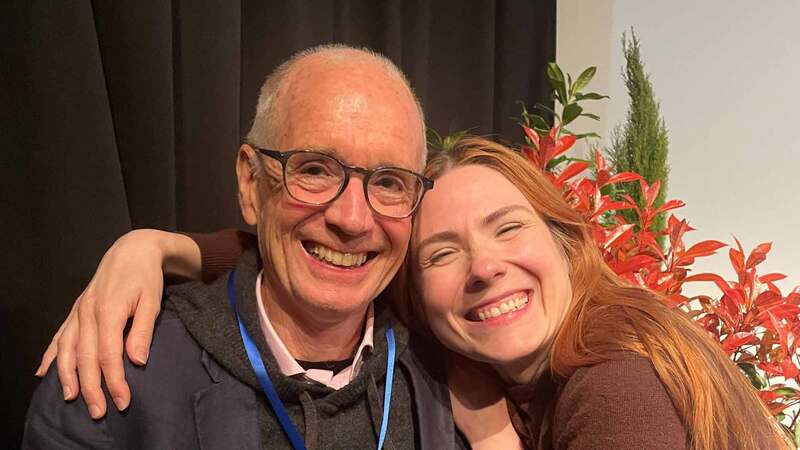

On 18th June, the third winner of the ADCI (Authors with Disabilities and Chronic Illnesses) Literary Prize, co-founded in 2022 by publishing executive Clare Christian and myself, will be announced at the Society of Authors’ awards ceremony. Three authors are shortlisted in a bid to follow in the steps of inaugural winner Nicola Griffith’s Spear (Tor) and last year’s victor, Lorraine Wilson’s Mother Sea (Fairlight).

From the genres of historical, literary and contemporary fiction, all three writers eschew outmoded disability stereotypes and engage with powerful stories showing the realities of living a disabled life. Here we spotlight the shortlisted authors.

Tom Newlands – Only Here, Only Now

‘There were no role models out there publishing stories like mine. I couldn’t find the novel I wanted to read, so I wrote it,” says Tom Newlands, debut author of 1990s Scotland-set, coming-of-age novel Only Here, Only Now. “I didn’t start writing until the age of 40, in large part because, growing up with ADHD, I didn’t feel my thought processes or methods of working were compatible with the production of a novel.”

Working as an autistic individual in a series of unadapted workplaces meant all his energy went on struggling to hold down jobs, with little left for writing. But when he was put on furlough at the beginning of the Covid-19 pandemic, it gave him the time to realise his creative ambitions. “I started the novel in April 2020, a few weeks into lockdown. I had taken a couple of poetry classes, but hadn’t written prose since high school, back in the mists of the 1990s. The manuscript won me a bursary place on a novel-development course and my agent [C&W’s Sophie Lambert] found me there. Along the way I have had the support of several organisations who are committed to supporting under-represented voices: Spread the Word, Creative Future and New Writing North.”

His teenage protagonist, Cora, is neuro-divergent and Newlands’ colloquial prose vividly evokes the way she restlessly experiences her surroundings and experiences. “I wanted a protagonist who found worth in the youthful junk of her existence, in the material of her life, but who was driven for something more. She’s 14, she doesn’t know what she wants, but she knows it lies beyond the limits of her crap town. The whole book started with her.”

Newlands is currently working on a second novel, a love story about two people with untreated PTSD who live in a crumbling new town. His aim? “I want to help other neurodivergent writers,” he says.

“The work that the ADCI prize does in shining a light on positive disability representation shows not only that these stories are worth telling, but that the lives and the working methods of the authors, however challenging or far outside the ‘norm’ they may seem, are valid and can produce work worthy of recognition.”

Helen Heckety – Alter Ego

Helen Heckety’s experiences of trying to find herself in her 20s as a young disabled woman inspired her debut novel, Alter Ego, which features Hattie, who enacts her scheme “The Plan” to move to Wales to start a new, non-disabled life where no one can know the truth about her. But for how long can she mask who she really is in the pursuit of who she desperately wants to be?

“I think the story appeals to everyone, because we are all trying to find ourselves in one way or another. I think it took a year or two to write – I’ve sort of lost track,” says Heckety, who adds that her agent, Hayley Steed at Janklow & Nesbit, “got” the novel from the off.

Heckety juggles writing with being an alternative comedy show and spoken-word performer and is writing a second novel. She hopes to keep writing fiction for as long as possible. The attitudes Hattie experiences in the novel, and her initial feelings that she must mask in order to “pass”, may be familiar to readers, along with her 20-something, sometimes comedic desire to find her place in the non-disabled world. “I’d love as many people as possible to read Alter Ego so we can really change the game in terms of ableism and representation.”

When asked how she thinks the publishing industry can better support disabled authors, Heckety’s first point is for it to recognise its lack of diversity. “Then I think publishers need to interrogate their own ableism – which, to be clear, we’re all brainwashed by because of our society. And then, with a good reflection on that, I think they will be feeling more confident in how to sell and promote books by disabled authors. If we don’t see ourselves, we feel like we don’t exist. If other people don’t see us, they act like we don’t exist. I think representation can literally be life-saving.”

Victoria Hawthorne – The Darkest Night

Victoria Hawthorne’s (writing career began in 2016 with a self-published collection of short stories. Since then she has released psychological thrillers and Gothic suspense under her real name Vikki Patis, before pivoting to historical mysteries with the pen name Victoria Hawthorne.

The Darkest Night begins with teacher Ailsa Reed escaping to the comfort of her grandparents’ house in Fife to find that her grandmother Moira, who has dementia, has gone missing. A chain of events links them both to a curse placed on the women in their family. “The very first image for The Darkest Night came from the iron ring in [Fife town] Kinghorn, which is said to be the place they burned witches – or rather, women – centuries ago. It was the perfect setting for the story that eventually came to be, though this book went through so many iterations. It took a good two to three years to get it anywhere near a decent state.”

The character of Selina, an ancestor of Ailsa’s, was inspired by Hawthorne’s own experience of disability. “I chose to give Selina Perthes disease, a condition I developed as a child and one I had never seen represented in fiction before. As rare as Perthes is, I have had people come up to me at events to share their experiences of it, and that, really, is the whole point: to feel seen.” She adds: “Seeing myself in stories is so important because it tells me that I’m not alone, and that my experiences matter.”

Hawthorne is currently editing a horror novel that is pitched as “Jennifer’s Body meets Carmilla” set in the Cabrach, a remote area close to where she lives in north-east Scotland. Previously, Hawthorne juggled writing with another career but since being made redundant in December 2024 she has worked as a full-time writer. “Despite the financial implications, I absolutely love it, so I’m hoping to keep it going for as long as possible.”