You are viewing your 1 free article this month.

Sign in to make the most of your access to expert book trade coverage.

The age of the anti-algorithm book

In a world of copycats and celebs, independent and indefinable books are winning out.

There’s no money! Reading is dying! Authors are doomed unless they’re a Prince or much-loved tall telly man! Amazon will algorithm us all to death and then sell our organs! ("customers who bought this kidney also bought")…

The publishing landscape can feel bleak. And let’s not tap-dance around the reality: it sometimes is. There’s the (deep breath) cost of living, struggling indie bookshops, floor-scraping author income and dominance of IP/celebrity memoir, all soundtracked by the crank-chug-chug of an algorithm demanding more, more, more, the same, same, same.

But is that the whole story? Nah.

Something else has been ignited, steering us into a purple patch for books hunting out the new, the different.

Do you feel it?

Back in the mid-90s, the industry enjoyed nine years of unit sales over $200m (£198.6m in 2023). And I turned 18 (1997). My seismic summer beginning in the wet days of June, and by the hot, sticky nights of August, I was changed.

That was the summer my first boyfriend’s parents passed me book after book – Michael Cunningham’s Flesh and Blood, Toni Morrison’s Song of Solomon, Cormac McCarthy’s All the Pretty Horses. Unexploded bombs in the palm of my hand. The world had never felt bigger. I went off the smell of Kouros.

Here’s what hasn’t changed since then: my belief in the power of books and specifically, the power of human choice, of a human choosing for you.

And here’s what has: every click is tracked, every pick interpreted as a "like", personalisation is anything but. And it isn’t just because I’m 104 in internet years (44 in real life) that I say the internet and social media own us like sheep wriggling under the farmer’s hot iron.

So, yeah, of course some of us thirst for alternatives. For the shadow of a human hand, the promise of the serotonin-shot delivered by discovery. For books that surprise, change you in unexpected ways; that make you want to run down the street bra-less, screaming chunks of the discovered book into the wind. For the anti-algorithm books, if you will.

There might be a few assumptions raising your blood pressure, so let’s go at ’em. No, I don’t believe the give-me-the-new-stuff-junkies are all middle/upper-middle class intellectual outliers (and it’s anti working-class to assume so); I don’t think the bold means the death of sales (Gordon Burn-shortlisted Megan Nolan, John Niven, Rory Carroll and Jonathan Escoffrey wrote bestsellers).

This binary view – experimental equals zero sales and engagement, while commercial is for "real" readers – is a false one (as is the position that the latter is trash and the former the real deal; that digital can’t be a tool when tuning into an analogue signal). This age has no truck with any of it.

This is the ultimate promise and power of the anti-algorithm book: it exists in a land that other publishers (and data) haven’t reached yet

As I write, the book pages are in a tizz about Sheila Heti’s Alphabetical Diaries, whose very process – journals cut into sentences, then put in alphabetical order – drop-kicks form, structure, the act of reading.

A few days prior, a tweet from Canongate’s Anna Frame: “Just hit one thousand preorders of a debut poetry collection through a single independent bookshop… Is that some kind of record?” The book was Poyums by Scottish poet Len Pennie, the orders driven by an audience she’d (unexpectedly) gathered on social during the pandemic through her lifelong passion for indigenous languages. A community, gagging for authentic, original work that speaks to them, who then buy from a loved indie.

Binary schminary. (Did I say 104? Probably closer to 124).

And it certainly doesn’t factor in one massive change: the sky-rocketing influence and impact of indies.

Fitzcarraldo Editions, Blue Moose, Galley Beggar Press, Daunt (who publish Kick the Latch by Kathryn Scanlon, a Gordon Burn-shortlisted title), Blue Moose, Jacaranda Press, New Directions Publishing, Nine Eight Books, Jawbone, White Rabbit (set up by Gordon Burn’s editor, Lee Brackstone)… others I can’t fit into the word count, don’t hate me.

These small and specialist publishers are grounded in an editor’s eye, gut and heart. Risk is not just welcome but baked in (which isn’t to say no-one else is doing it – Faber’s film and music lists are worth a look right now, for example). They ensure traditional forms continue to evolve.

And they’re not just publishing new writers, but the established, too. Their ambitions are up big in widescreen. They punch well above their weight in book prizes – and not just the Gordon Burn and the Goldsmith, which were set up for such work, but the likes of the Booker, won by Oneworld’s Paul Lynch in 2023 and Shehan Karunatilaka of Sort of Books in ’22.

But perhaps there’s something more important in the shift: the freedom that risk-takers and rule-breakers offer writers, especially those not published historically. Who may not want to walk in the footsteps made by another’s weight (and long for the day they’re not asked, “but is it/she/him relatable?” To who, mate? You?).

In the ashes of convention lies the chance for them to build something authentic. Their voice. Their words. Expressed their way (like the use of mythology, music, poetry, and illustration in And Other Stories’ Split Tooth by Tanya Tagaq).

This is the ultimate promise and power of the anti-algorithm book: it exists in a land that other publishers (and data) haven’t reached yet. A land often reached only by humans: a trusted bookseller, a lover, a friend, a publisher, a neighbour. They return with an unexploded bomb. Place it in your palm. And the world changes.

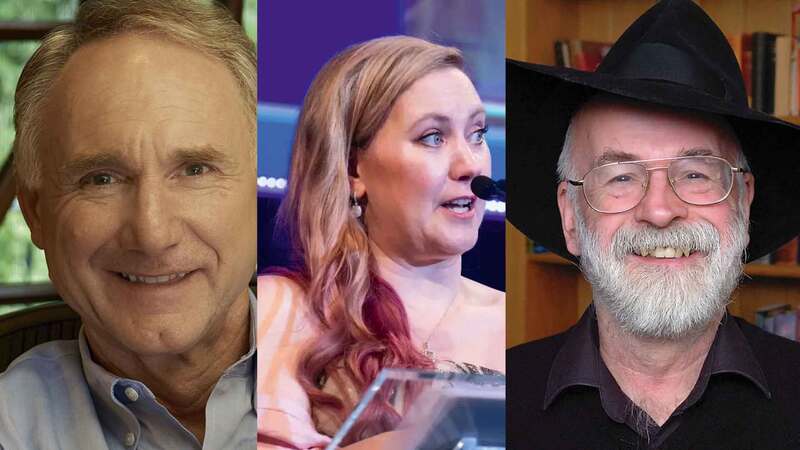

The winner of the Gordon Burn Prize 2023-24 will be announced on Thursday 7 March at the Northern Stage in Newcastle