Saving endangered languages

At least half of the world’s languages are under threat, and we need more books to help.

Teaching children about endangered languages matters. Unlike endangered species, endangered languages disappear because people can’t see a relevance for their children to speak them anymore. When a new generation of speakers, and their parents, only see aspirational opportunities in a majority language the message is clear; their native tongue does not belong in their future. This choice is not entirely their own and as professionals that work in publishing, we have a role to play in that.

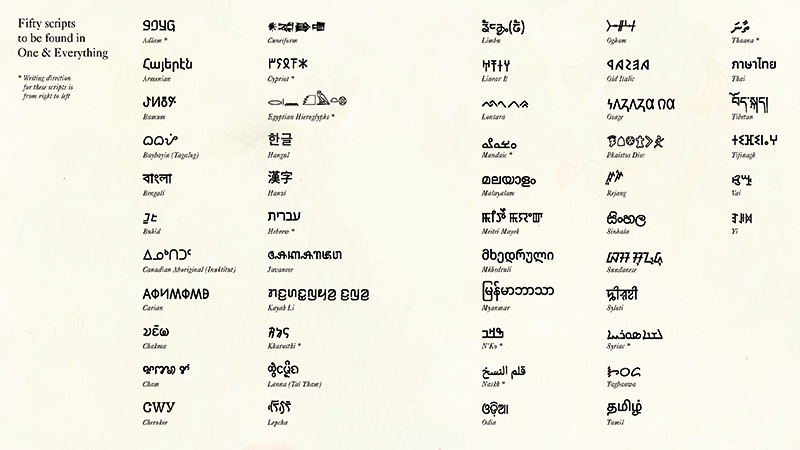

While working on my latest picture book and an upcoming children’s art trail at the Southbank Centre, I began to focus on some of the languages that have unique writing systems. Incorporating over 50 different scripts, it opened my eyes to how stunningly beautiful these languages are and how children are key to what happens to their future.

When training in design, I was often amazed and slightly puzzled by the almost infinite amount of typeface choices I had available. But it took me another decade or two to ask: why are there so many fonts in just the Latin script? If, like me, your native tongue is a majority language, the experience of seeing it everywhere, conceals the fact that other languages aren’t appearing in that same space.

Of these estimated 6,500 plus languages, roughly half of the world’s population speaks just 25 of them. But as the Endangered Languages Archive states “Today there are about 6,500 languages spoken worldwide and at least half of those are under acute threat to not be spoken anymore.”

The human story is only rich and compelling if we maintain all the contrasting ways in which we can tell it

A majority language can carry the aura of employment and mobility which is a major factor in whether children (or parents) deem their heritage language as equally valuable. Seeing popular culture in one language carries a powerful message. Yet the opposite is also true, a rarely seen script or unheard voice in mainstream media is not only a point of pride for those communities, but also a reminder of the depth of culture that is already here in our human family.

When fact checking the book One & Everything, we had to contact many readers and it was deeply humbling to receive responses such as Shareehan Ibrahim’s “…you can imagine my absolute delight when... [you] first contacted me... I hope I am somehow successful in conveying just how much this has meant to me. Thank you so much for this opportunity to discuss Thaana with you.”

I encountered this enthusiasm repeatedly when I asked people to share their knowledge. Shareehan herself makes beautiful picture books in the Maldivian language Dhivehi (using the Thaana script) and there are many great individuals and organisations like hers. Tim Brookes has an online Atlas of Endangered Alphabets (with an array of beautiful scripts) and the Endangered Languages Archive has a digital repository that is a brilliant resource to explore.

But none of these endeavours succeed unless we also have the creatives and storytellers to bring these words to life. Data goes only so far before the spark of the arts, literature and culture must set it alight.

Adlam was invented in 1989 by two brothers, Abdoulaye and Ibrahima Barry, who decided that their language, Fulani, needed its own alphabet. They were still in school at the time, but that didn’t stop them from sketching symbols they thought would work. Adlam is remarkable both for the ages of its inventors and for the speed at which it moved from a handwritten local script to one that is now used on phones and computers around the world.

The Adlam alphabet gets its name from these first four letters (in English they are the letters A, D, L, and M, read right to left), which stand for Alkule Dandayɗe Leñol Mulugol, meaning “the alphabet that protects the people from vanishing.”

It’s the bold imaginations of these young people that are so necessary for any cultural flourishing.

This localisation of culture also reinforces that the language is of real consequence now. In researching the book, I also found quite a few studies observing clear correlations between language diversity and biodiversity. It’s not as if the solutions to some of our most pressing problems aren’t directly related.

When making picture books you learn, in part, how to tell the story through colour and tone. Contrast is a beautiful way to explain things beyond what one colour alone can say. The same is true for languages: the human story is only rich and compelling if we maintain all the contrasting ways in which we can tell it.

Creating opportunities for diverse young voices is key to what happens next. Both this book and the trail are invitations for all of us, young and old, to travel the planet and learn about the world’s languages and the people that speak them.

One & Everything Family Trail takes place at the Southbank Centre’s Imagine Children’s Festival from 8th – 17th February. Tickets are free. One & Everything is published by Walker Books.