You are viewing your 1 free article this month.

Sign in to make the most of your access to expert book trade coverage.

Autism is not a genre

The book trade needs to approach autism in much deeper and more nuanced ways.

In the past, there wasn’t nearly enough awareness about autism, so the fact that it has become more present in public discourse over recent years feels like a positive development.

Except… this new awareness also seems to be manifesting in a deeply problematic way. Reform UK’s deputy leader, Richard Tice, has recently controversially described children who wear ear defenders in school as "insane". Then there’s the discussion around autism diagnoses "skyrocketing" – surely an inevitable consequence of greater public awareness and better clinical knowledge, except there is an implied message that these diagnoses aren’t necessary when, for many, they’re a lifeline.

From vaccinations to Tylenol, the misinformation and dismissal around autism is insidiously frightening in a world where research has shown that one in four autistic people have attempted to end their life.

There is, of course (if you want to find it), real, studied information about autism out there. There may even be a disability section at your local bookstore – and though there is still a lot of room for more nuanced, deeper research, you’re probably more likely to find a book on autism than other disabilities, which speaks to the shocking lack of disability representation as a whole.

A lot of these books, however, are still only dealing with the effect that autism has on other (often non-autistic) people in real life – some of these books are well-intentioned and may be helpful, some are less so, but there could be so much more than this, especially in fiction. Perhaps this is part of the problem – when the concept of diversity is treated more as a tickbox than an opportunity to expand the way we think about writing, creativity and the world in general, it can feel a little stagnant.

This is why it’s vital for us to read, publish and listen to autistic individuals more than ever before. It shouldn’t be just about ticking the box of autistic representation – though there are recent releases such as Caroline Peckham’s Hollow, Deandra Davis’ All the Noise at Once and CG Drews’ Hazelthorn with interesting and complex takes. We must also consider access for autistic writers in every aspect of publishing, from the way we talk about craft to how editors work with authors. By exploring and questioning the expectations we place on autism, whether that’s as a small quirk, a superpower or something to be avoided or feared – both inside and outside of books – we open ourselves up to a restructuring of the world of literature; a revolutionising of narrative and storytelling across genres by not always conforming to literary standards set, predominantly, by non-autistic people.

When the concept of diversity is treated more as a tickbox than an opportunity to expand the way we think about writing, creativity and the world in general, it can feel a little stagnant

For example, Dr Clem Bastow, editor of the UK edition of Someone Like Me – an anthology of personal essays by gender-diverse and women autistic writers – and a senior tutor in screenwriting, reflects: "I realised that there were many things I did as a writer that were often deemed to be ‘wrong’ or would be cut back by editors even though they were really crucial to my ‘voice’ as a[n autistic] writer."

Co-editor Jo Case, senior deputy editor of Books & Ideas at The Conversation, recognises the way editing can be a place where autistic thinking shines: "When I learned bottom-up processing was an essential part of being autistic, it made so much sense to me, as it’s how I experience the world – and why editing comes naturally to me. I experience the world by intensely focusing on details and piecing them together to form a big picture."

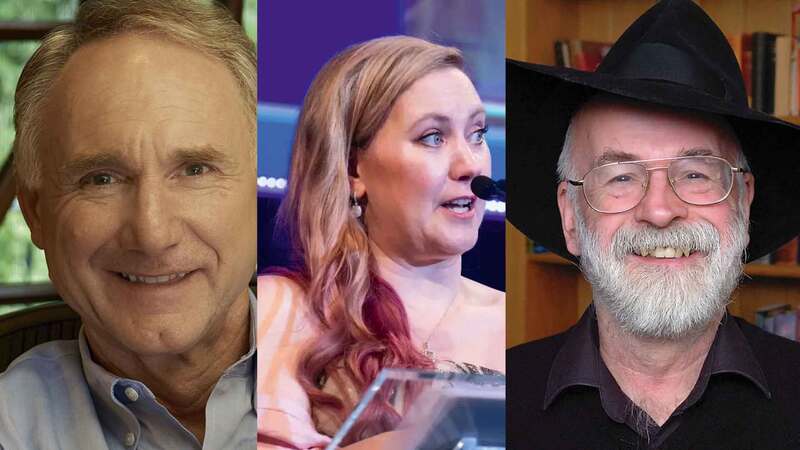

Meanwhile, for Sunday Times Bestselling author Lucy Rose, her autism – and ADHD, a common comorbidity – has a huge impact of the way she writes, and how much she can do in a day, sometimes negatively: "For me, writing only happens in very short bursts before my focus shifts. That’s exactly why the chapters in The Lamb are so short, because that was literally all I could manage before my brain goes into the extreme of what I call ‘neurodivergent knots’ or ‘zero activity/paralysis’.

"This is a state where you can’t move or speak. You become so overwhelmed, you shut down or sometimes, have a meltdown – which is where the stress hangs on the exterior rather than the interior. At its extreme, it can result in emotional fits or physical self harm."

Autistic individuals are all different. With autism affecting the way we view the world and the way we live our life so thoroughly, why shouldn’t we see that reflected in art? We need diverse and authentic depictions of autism; more intersectional representation, stories outside of the autistic savant, of autistic joy, adventure and, yes, also sometimes tragedy.

Reading, after all, can often be an act of resistance, and with a common refrain from autistic people being an indescribable feeling of otherness, stories can be a way to feel less alone. For those outside of the autistic community, they can be a way to go from beyond awareness to understanding… and, often, just a damn good book you might enjoy. Autism, after all, is not a genre.

Internationally bestselling and award-winning author of teen book series Geek Girl, Holly Smale, (whom I would read late into the night, back when the feeling of difference didn’t have diagnostic name yet for me) sums up the reason we need to read autistic authors now more than ever. "The idea that I might accidentally harm other autistic people – how they see themselves, or how others see them – regularly gives me sleepless nights. But I try to remind myself that this is not something that neurotypical writers tend to worry about: the fact that they’re writing about individual humans goes without saying, which is an unseen privilege of being considered ‘normal’.

"We all know that one fictional character can’t possibly represent millions of strangers, so why should autistic writers (or any other minority writers) carry that weight? We can only write from our own flaws, pains, joys, difficulties, strengths. Autistic people are likeable and unlikeable, just like all humans. It’s important that we allow them to be that on the page too, without flattening them for fear of reprisal… ‘Likability’ isn’t really very interesting to me. Honesty is."

Reading allows us a window into unique experiences and worlds. I urge you to buy, borrow, pre-order and discuss books by autistic authors, to encourage publishing to continue making more windows, not to bar them up.