You are viewing your 1 free article this month.

Sign in to make the most of your access to expert book trade coverage.

Are influencers harming the book industry?

The overvaluation of influencers in commercial publishing has real impacts.

I am of the opinion book influencers and commercial publishers are promoting an unhealthy approach to reading and reviewing that is affecting the culture at large.

Not all books should be produced, consumed and reviewed in the likeness of fast fashion. In writing this piece, I came across Soaliha Iqbal’s Instagram reel on the "Sheinification" of books – I second everything she says. I believe in letting art sit with you and affect you over time. Art deserves space to develop and to be processed.

Couple this with first-hand experience of how white, middle-class(-adjacent) folk who review our books with no sense of curiosity nor willingness to understand, perpetuate ill-judged and ignorant perspectives. Even the bit-of-fun, dramatised, just-my-personal opinion pieces can, and do, reinforce casual classism and racism in the book industry. I say this as a working-class publisher and writer of colour, with ample lived experience of classism and racism.

This speaks to my issue with commercial publishing’s relationship with book influencers. Unchecked bias oils the capitalist machine of book production.

Bookwormbullet Ayushi’s impression of a white Booktoker’s top 5 books is such a brilliant example. Might it be that books from writers of colour, reviewed online by young, white, middle-class influencers are too often devalued, trashed or engaged with superficially? It is not typical of a publisher to comment on book reviews, and it is not something I would encourage or wish to repeat, but I feel I have been personally invited in this instance, as someone whose books most suffer from this treatment.

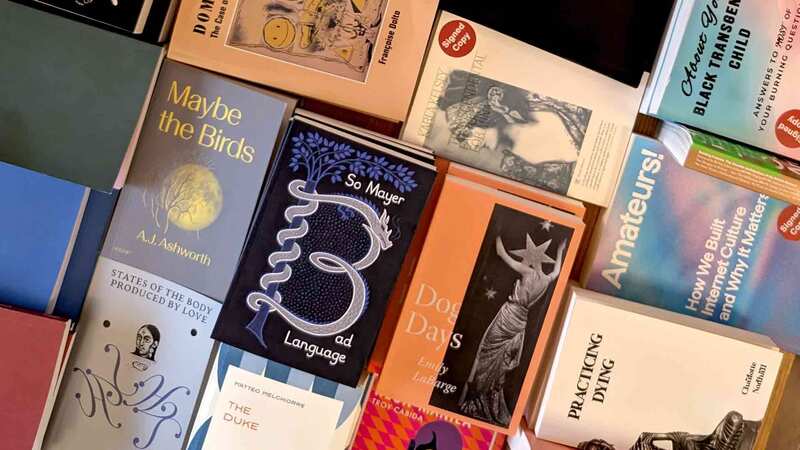

Everyone is welcome to their opinions on books, to question how books are commissioned, to assess their quality, and evaluate their contents. But, when influencers, authors and other publishers question why I publish what I publish because it is not their preference, because it is not literary, not obviously "commercial" or "good", my easy answer is: This book wasn’t written for you. You are least likely to relate, to value this voice represented in traditional publishing, to understand the historical significance of this book in the Welsh literary landscape. You live in a classist language system that assumes certain lexical choices indicate depth and intelligence. In other words, bigger words and complex metaphors equals better, more satisfying writing. Maybe, but GCSE English Language has something to say about establishing your audience. Better and more satisfying for whom?

Nurturing sincere and authentic voices is key in a world full of the posturing, performance and pretence that is slowing down real change

Nurturing sincere and authentic voices is key in a world full of the posturing, performance and pretence that is slowing down real change. It is radical to resist making yourself palatable and acceptable to people who care least about you and your art. That energy is better spent making art for people you care about.

Books may evade every possible standard we have, so it behooves the reader to understand what their standards actually represent, especially when applied universally.

My issue is this: too many book influencers (non-exclusively) profit from casual classism and racism. Those who never interrogate their biases reinforce them, making things worse for society overall. I am concerned about the negative impacts of the weak and, frankly, bad review culture that has emerged from social media, which informs what gets picked up by agents and presses, what sells, what is marketed, how and to whom. This is intensified by the "Sheinifaction" of the industry.

Not all books are for all people. However, the people at the centre of the world – the loudest, the most visible, who designed the world to be this way – have resources to spend on books, to write books, to publish books, to review books, to market books. Consequently, books are geared to them, with all the exoticisation and fetishisation, neglect and ignorance that comes alongside, at every level. In my view, that is poor culture-making, because stories are universal. We could all enjoy more variety in traditional publishing across all genres if people at the centre contributed less white noise, and tuned in to our frequencies for a while.

Without introspection about how standardised tastes are acquired, this generation of centralised tastemakers – who can afford to take social media opinions and sales figures at face value – will perpetuate the cycle. They will decide what books do not get agented, don’t get published, don’t get commissioned.

I am not saying if a book isn’t written for you, you should not read and review it. I am saying, on books that might not be your preference, question why that may be. Change your approach. Engage accordingly. If you care about accessibility in the industry, look again at your own output. Be willing to meet unfamiliar writing styles and themes with curiosity, humility and understanding.

Ultimately, I am asking those who experience privilege and gatekeepers of all varieties in the book space, reviewers to agents, booksellers to funders, to question your assumptions – something that requires us swallowing our egos, the ones that have gotten us this far, in a system designed to advance some people’s success at the expense of everyone else.