Tomi Obaro in conversation about Nigerian weddings and unconventional love stories

“I’ve always thought that that was an interesting source of drama and have been surprised at how little fiction has engaged with what is the pageantry of a certain kind of very opulent Nigerian wedding”

Tomi Obaro

Register to read for FREE.

Serious about the book trade?

Join thousands of book industry professionals who never miss a story.

Create a free account to unlock 3 articles a month and receive tailored newsletters with the latest from the book trade.

Want full access? Subscribe from just £3.65 a week and unlock full access to exclusive interviews, rights deals, industry data and more:

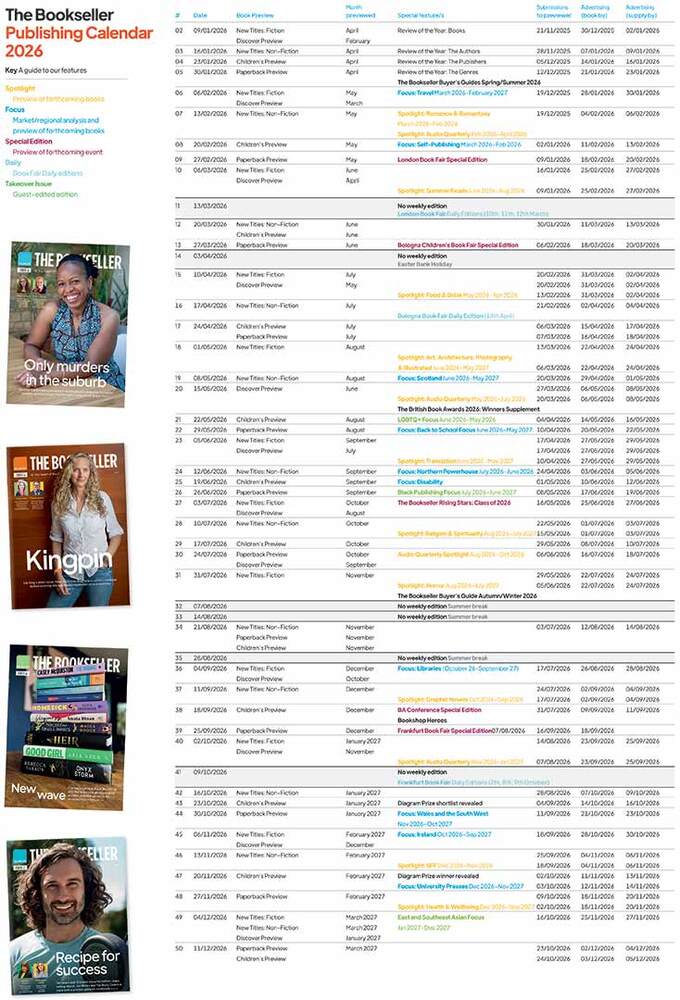

🗞Weekly print copies of The Bookseller magazine

📱Unlimited access to thebookseller.com (single user)

👨💻The Bookseller digital edition for desktop, tablet and mobile

💌Subscriber-only newsletters

📚Twice-yearly Buyer’s Guides worth £30

💡Discounts on events and conferences