Nicola Barker's comic new novel poses profound questions about authenticity, art and honesty

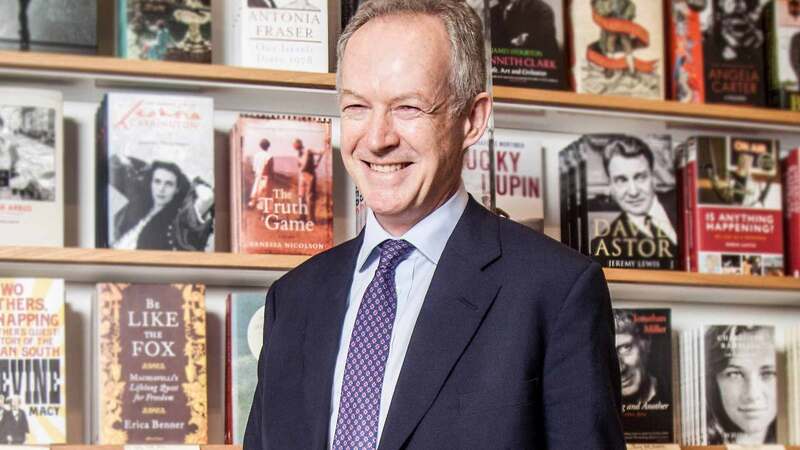

Alice O'Keeffe

Alice O'KeeffeIn a nutshell, I read books for a living. I interview authors for The Bookseller's weekly Author Profile slot and write the monthly New

...moreThe Goldsmiths Prize-winning author talks about her 14th novel, TonyInterruptor, and why she never looks back at her career.

In a nutshell, I read books for a living. I interview authors for The Bookseller's weekly Author Profile slot and write the monthly New

...moreRather endearingly, Nicola Barker has no idea that TonyInterruptor is her 14th novel. She wonders if I have included her two collections of short stories in that number? I have not. She hoots with laughter: as I discover over the course of our lunch near London Bridge, Barker, who is riotously entertaining company, is an author who lives and writes firmly in the present.

While she does not particularly care to look back at her career – “I honestly don’t do it. I wish I could take pleasure in it but it’s just not the way my mind works. It’s like someone else’s life” – she had published five novels, including Wide Open, which won the 2000 International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, by the time she was selected as one of Granta’s Best of Young British Novelists in 2003. Her 2007 novel Darkmans was shortlisted for the Booker Prize and, more recently, H(A)PPY scooped the Goldsmiths Prize in 2017, an honour awarded for fiction that “breaks the mould” and extends the possibilities of the novel form.

Which is something that Barker has always done, seemingly effortlessly. Her writing is variously described by critics as “avant-garde”, “anarchic” or (my favourite) “bafflingly innovative”, but her books, she says, are about“just the things I’m interested in at that time…a kind of working out for me. I am very interested in the culture and what it’s doing so I’m always thinking about where it will go and what would happen in particular scenarios. It’s hard doing that because, yes, there is the danger that things become unfashionable very quickly, but I’ve lost interest in them by then anyway, because I move on”.

TonyInterruptor opens with a heckle during an improvisational jazz set starring trumpet player Sasha Keyes and his Ensemble, in front of a rapt audience: “Is this honest? Are we all being honest here?” asks the man who will be christened #TonyInterruptor when a teenager filming on an iPhone captures the moment and posts the clip online. #TonyInterruptor goes viral and the novel traces the aftermath of the incident on a small group of characters, among them the enraged Keyes, whose music-making integrity has been insulted; Fi Kinebuchi, player of the autoharp and lyre; her university colleague Lambert Shore (whose daughter India is the teenager with the iPhone) and his “magnificently quarrelsome” wife Mallory.

The idea for the novel came about when Barker was at a musical performance and thought to herself: wouldn’t it be funny if someone just stood up now and said something, and became part of the performance? “I’m so interested in interruption, the nature of interruption in modern culture, what it means. What’s beautiful about it but also dangerous and devastating. It seems to be a very important thing. It’s certainly important for me because I’m a terrible interrupter by nature. I interrupt my own work; I’ll start a book and then interrupt it. I never watch a film all the way through. I don’t do anything in a very thorough way; I’ve always been like that. There’s a kind of chaos to the way I live through things. So, it always interests me when the culture starts to reflect something that I’ve always considered a terrible fault in myself.”

Continues...

Subsequent events are a vehicle for Barker to explore some knotty questions with humour and playfulness: about honesty in the internet age, cancel culture, the difference in attitudes between the generations, how is it possible to be authentic and what does authenticity even mean? “In some ways [the novel] says absolutely nothing, there are just people having conversations with each other, which is perhaps the only safe way to do it. But at some level I suspect I’ve always done that, dealt with thorny issues but in a very indirect way. Often because I don’t really entirely know what I think about things myself, so it’s not like I have some huge statement to make, I’m just trying to ponder these things, make sense of them. Just to allow that conversation to take place, that’s the most important thing.”

TonyInterruptor is Barker’s first novel with Granta and reunites her with editor Jason Arthur, who published her at William Heinemann. Barker has always carved her own path, aided by her first agent, the late David Miller –“he never put any pressure on me to do anything other than what I wanted to do. He was wayward, a madman. I loved him” – and now Matthew Marland.

But, as she tells me, she nearly stopped writing altogether after H(A)PPY: “It was a whole drama for me around the meaning of the novel and whether I had anything else to say. Everything imploded for me, in my private life, in every way.” She moved out of London to Faversham, Kent and, in lockdown, while the rest of the world decided to have a crack at the novel they had never got around to, Barker lost all desire to write. She took a job in a local charity shop – “I thought, well I need to earn some money” – where she had previously been a volunteer, which she finds both rewarding and a wonderful source of people-watching.

“Writing had always been such a source of pleasure for me, and also an escape,” she explains. But she “didn’t want to live in fantasy any more. I wanted to actually hatch into real life, which is sort of what I’ve done. So, the move back to writing again is a controversial one in my mind. It gives me pleasure but it’s not the same kind of drive that it used to be.”

One of the questions the novel asks is: how free is it really possible to be? In life, in art, even in free jazz? It is a question that has fascinated Barker for years. “We are divided selves between our conscious and unconscious minds and the unconscious dictates so much.”

She recalls reading Henry James’ The Portrait of a Lady at university and found it “so impossible to understand, so hard to read and so unfriendly in terms of its grammar and structure. And yet, as I battled through it, there came a point when I suddenly started to sob. I’ve no idea what – I’ve not read it since – but something hit me so profoundly, some great truth, and only the novel could somehow have been able to bring that about. It had been a struggle and there had been interludes of complete incomprehension, yet it did something so deep to me that I’ve never forgotten it. That’s intriguing to me”.

“So much in life is incomprehensible and sometimes I feel novels are there to make it comprehensive, for me at least,” she says. “But all of the most magical things in my life are hard to describe, the most profound moments, and often they are operating at an unconscious level, or subliminally. When that is happening you just want to try and engage with it.” She laughs. “It doesn’t make my books sound any more readable does it, when I say stuff like that?” I disagree: her novels are brilliant, inventive and hilarious. Much like the author herself.