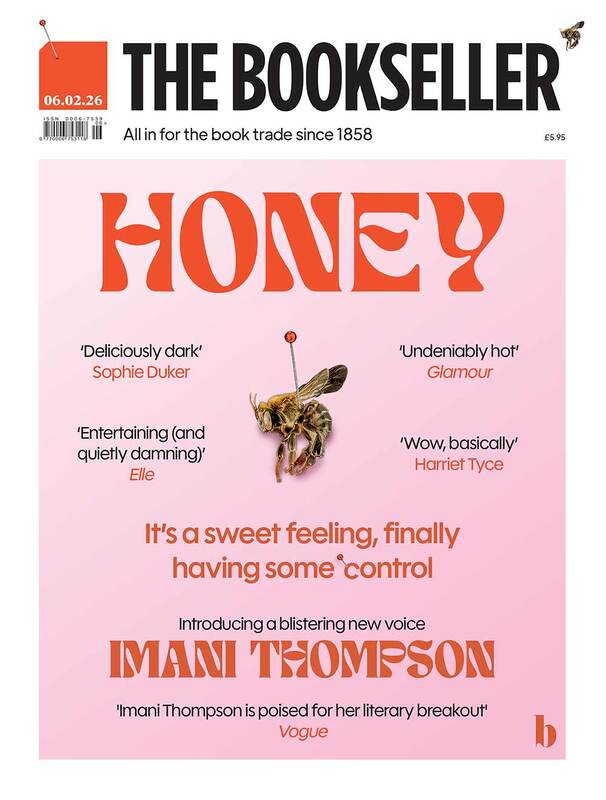

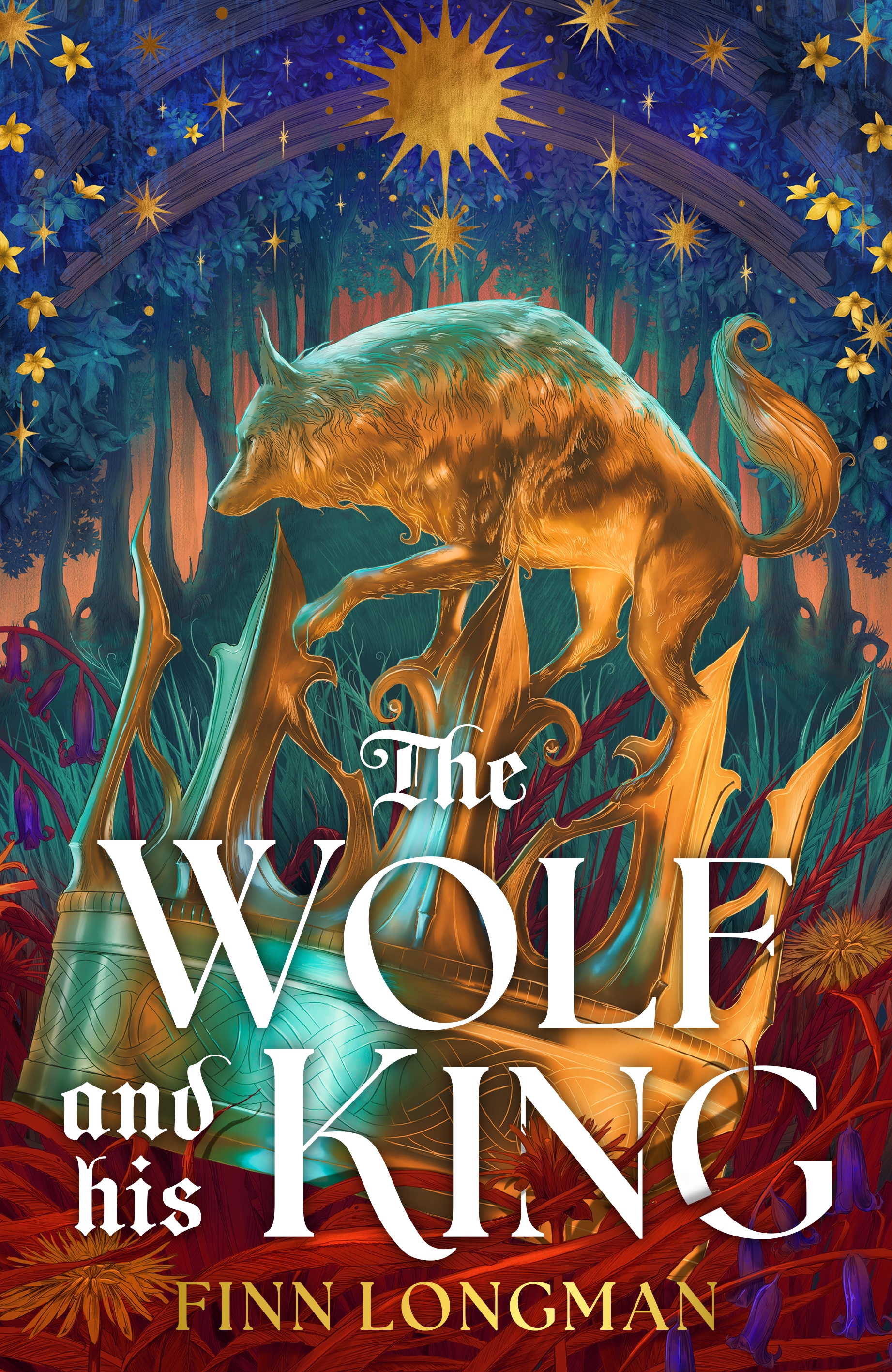

Finn Longman's adult fantasy debut is a story of love, yearning and grief

Katie Fraser

Katie FraserKatie Fraser is The Bookseller's staff writer and chair of the New Adult Book Prize. She has chaired events at the Edinburgh International

...moreMedievalist and YA author Longman makes their first foray into adult fantasy with a retelling of a 12th-century tale about an exiled werewolf.

Katie Fraser is The Bookseller's staff writer and chair of the New Adult Book Prize. She has chaired events at the Edinburgh International

...more"A lot of modern werewolves stick to the full moon, so it’s predictable and you know when the change is going to happen,” explains academic and author Finn Longman. The werewolf they have created is different.

The Wolf and His King, Longman’s retelling of the medieval story of Bisclavret from the lais of Marie de France, features a man – Bisclavret – who never knows when he will transform into a wolf. His shift is not tied to the moon, nor has any discernible pattern.

During the 12th century, when de France wrote the original tale, werewolves were “frequently [portrayed as] quite sympathetic figures. They seemed to reflect a lot of anxieties about identity and what it means to be human,” says Longman, who first became aware of the tale, and its intersection with academic queer theory, during their second undergraduate year at the University of Cambridge.

After a sojourn at University College Cork to complete a master’s, they are now back in Cambridge working on a PhD on friendship and affection in the late Ulster Cycle, a body of medieval Irish mythology.

“It can feel like my academic reputation is on the line... There is this anxiety I have to prove myself as a medievalist as well as an author,” says Longman, whose previous YA trilogy had nothing to do with their academic work.

I lost a really fundamental part of my identity, and I lost the ability to write for a bit. I lost all this control over who I am and what I did and I was in a large amount of pain

I try to assuage their anxieties. To any reader, it will be clear that The Wolf and His King fizzes with Longman’s expertise and love for the original tale. This work, Longman hopes, stands in counterpoint to the tranche of retellings that they think were “written less out of care for the original story and more out of disdain”.

They continue: “Sometimes I read things and I’m like, ‘You think the original story is defective. You’re retelling it because you think it sucks, not because you love it and want to do something new with it’. I find that often makes for frustrating reading, especially if it’s a retelling of something you love.”

Longman describes retellings as like the “experimental archaeology of literature”, explaining: “People who do experimental archaeology will be like, ‘Oh, we don’t know how this tool worked, we’re going to make a replica and try and find out.’ What I do is think, ‘I don’t know how this story works. I’m going to tell it, find out and get inside the story.’”

In The Wolf and His King, Longman stays faithful to the setting and historical period and fleshes out the emotional nuance of de France’s verse tale to depict bodies and minds ravaged by pain and yearning.

In the novel, Bisclavret is coaxed out of his self-imposed exile by his cousin to attend the court of the newly crowned king in the hope of having his father’s lands restored to him. The king, shaky on the grounds of his new power, is enthralled by Bisclavret, this rugged man so different from the other gentry who grace his halls. The stage is set.

Continues…

The story unfolds through three perspectives – Bisclavret’s in the third person, the king’s in the second person and the wolf’s point of view written in verse – as Bisclavret attempts to rejoin society.

Bisclavret’s shifts into the wolf are unpredictable and uncontrollable. The change is incredibly visceral. “He snaps back into his own body with the ricochet of a broken spine locking into place,” writes Longman. Elsewhere, “his spine shatters, his neck breaks, and his body remakes itself into something unholy”.

For Longman, werewolves are “fundamentally defined by the loss of control over their own body” and Bisclavret’s condition, for them, became a “disability metaphor” and a way for Longman to write about their own chronic pain.

At the age of 17, Longman “developed debilitating chronic pain” in their hands. Up to that point, they had played the violin for a decade and “suddenly I couldn’t play...I lost a really fundamental part of my identity, the idea of me as a musician, and I lost the ability to write for a bit. I lost all this control over who I am and what I did and I was in a large amount of pain”.

Twelve years on, Longman now plays in local pubs on folk nights, but they still live with the pain as well as fatigue and migraines. Their chronic pain and their relationship with their hands contours Bisclavret’s experience shifting between human and animal.

“Every single time he comes back [to human form], he’s wondering when the wolf is coming next. When you have a long period of health, you’re always waiting, you’re always braced for impact... One of the things I realised when I was writing the first draft was every time Bisclavret transforms back into a human he’s grateful to have his hands again.”

However much he would rather the reverse, Bisclavret comes to realise it is impossible to live without the wolf, but he begins to understand that he does not need to exist at the margins, nor does he have to be alone. It is a realisation tinged with grief.

“A lot of my feelings about disability are very much grief,” says Longman. “Grief for lost opportunities, grief for other versions of myself that don’t exist anymore, grief for those things that get taken away from you when you’re not in control of your body.”

But there is a light and Bisclavret sees eventually there is someone that will seek him out in his worst moments, bring him back and love and care for him.

“A lot of Bisclavret’s narrative is about the moments when you are unable to participate in society and for people not only to wait for you to come back, but to go looking for you and to want you even when you can’t be a part of things.”

Longman disclosed in their blog that the novel has a happy ending because, they tell me, “there was so much darkness around me and I didn’t want to write hopelessness anymore”.

Forces bring the king and Bisclavret together, but it is not without tribulation or danger. The love that crackles into being is one that we all aspire to – an unconditional love from someone who sees you in your darkest moments and resolutely continues to love you.

“I think being loved in your worst moments is something I write about a lot,” says Longman. “Bisclavret has internalised this idea that he is unworthy of love. I think having to accept love can be very difficult sometimes.”

The Wolf and His King will enchant readers with its nuanced exploration of bodies, kinship and love. This may be a tale about a fearsome wolf, but it is not a story about a monster.